Published in Ahram Online on April 10, 2013

Art and poetry, more than politics, express the true spirit of the Egyptian revolution, which cannot be concealed or silenced

Scene I: Tuesday, 25 January 2011 at 7pm. Place: Tahrir Square.

I had gone to Tahrir nearly two hours earlier to check on my sister. She had beaten me there and had succeeded in foiling an attempt by security forces to arrest her 15-year-old son. After I had made sure that she’d go home, and after I’d lied to her telling her that I, too, would go home, I joined a crowd of about three or four thousand people at the corner of Mohamed Mahmoud Street.

It was there that I heard for the first time the iconic slogan of the revolution. Initially, I could only figure out the first two words: “Al-Shaab yurid” (the people demand). Before I could figure out the rest of the slogan (and I have to confess that I had missed developments in Tunisia where that slogan had already made its imprint), I realised what I was witnessing was already momentous. For one thing, the crowd had grown so much in size that a shift to classical Arabic seemed necessary. For another, the people were not “pleading” or “requesting”, but “demanding.” And when I finally figured out what they were demanding, I felt a shudder run through my entire body. Then the words of the famous poet, Abu El-Kassem Al-Shabbi, which I had memorised from my school days, rushed to my mind and it seemed as though I was hearing them for the first time in my life.

I realised that poetry is able to move millions and that, just as El-Shabbi had predicted a century ago, we would not wait for long until destiny obliged the people’s demand.

Scene II: Friday, 28 October 2011 at 10am. Place: Zenhom Morgue.

The first thing I saw was a young man in his 20s in a heated phone conversation. “We insist on a post mortem examination. He will not be buried except after an autopsy.”

I had arrived at the morgue with Nadia Kamel and Karima Khalil in solidarity with the family of Essam Atta who had been arrested by the military police and unjustly given a two-year sentence by a military court. While serving his sentence in Tora Prison, he was tortured to death by officers of the interior ministry.

The father was dazed and could not utter a word, the mother devastated. The brother was arguing with his uncle on the phone, insisting on his right to know what had happened to Essam.

But it was the sister’s words that captivated me. She had stopped crying, but her lamentation was the saddest words I had ever heard in my life. I had read about this public lamentation before in books, but I had never heard it before.

Her lament was more like poetry. It had the power to draw us in and engulf the entire world in a deep sea of grief. Soon we found ourselves with her in a vast barren desert where she shared with us her sorrow for not seeing her brother ever again.

Scene III: Monday, 21 May 2012 at 4pm. Place: same spot in Tahrir Square.

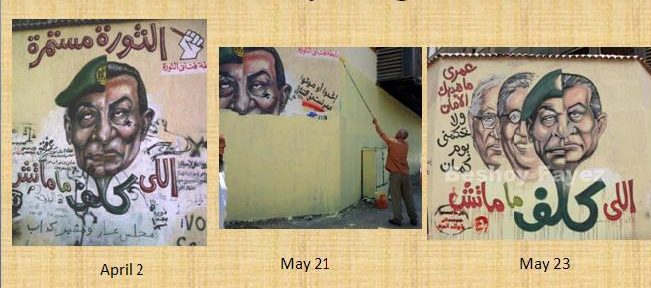

This time the revolution expressed itself in pictures rather than words: graffiti of a face that was vertically split in two, the right half for Mubarak and the left half for Field Marshall Tantawi. Above the split face was a phrase with a clever pun: “Whoever delegated has not died.” On that day the governorate sent one of its workers to cover the graffiti with a pale oily paint. Hours later the same graffiti reappeared, but with two additional faces, those of Amr Moussa and Ahmed Shafiq. Later still, Mohamed Badie was added to the pantheon.

Ever since the revolution, Cairo has been transformed from a city that never knew the art of graffiti to a city whose walls are now covered by witty, clever drawings.

Here art is not expressed in words, but by a confident brush or stencil. The amazing graffiti that now adorns the city reflects complex ideas that are infinitely more clever and articulate than official political pronouncements, talk show ruminations, journalistic musings or academic pontificating.

What art expresses here is a revolutionary sense of humour, revolutionary because for the first time our satire is not directed at the self, but at the other: at Mubarak, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the feloul, octogenarian politicians, and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Scene IV: Sunday, 31 March 2013 at 12 noon. Place: the Office of the Prosecutor General.

This time art is the culprit. The charge is literally incredible: insulting the president. The evidence against TV host Bassem Youssef is his own words recorded in his comic-serious programme El-Bernameg (The Programme).

In the 19th episode, Youssef thanked the president for sparing him much effort when preparing his programme, for the president’s own speeches and gestures have provided Bassem and his team with more than they need to come up with a witty, farcical show. Youssef and his team could have focused on the president’s repeated statements about fingers, statements that are clearly suggestive of what goes on in the president’s conscious and subconscious mind.

Yet, Youssef refrained from doing so. Still, he found himself accused of what he did not say and held accountable for what he merely alluded to using the president’s own words and insinuations.

Scene V: Saturday, 30 March 2013 at 12 noon. Place: Hall 13 in the English Department at Cairo University.

The US poet Tom Healy is delivering a lecture on “poetry and the revolution.” The lecture is profound and complex. The students are listening attentively. You could hear a pin drop. The Q&A lasted for nearly an hour. “Where does the poem come from?” “Where does it go after the poet delivers it?” “Who has the right to interpret it?” “What is the relation between poetry and anxiety? Hope? The revolution?” What captured my attention is the students’ self-confidence, their ability to express themselves accurately and eloquently. It seemed to me that they had a better knack than their professors in reconciling themselves with the world, with their society.

They know that they are in revolt, but it is a revolt against the regime, not against the whole world. Their contempt for the president is evident, his name and that of his group were not uttered once. It is as if art, and poetry in particular, has finally provided this generation with what it has been long seeking.

When I returned home that day, I pulled out Mustafa Ibrahim’s anthology Manifesto and poured over it until I realised that this revolution is not only a revolution of youth, but also a revolution that expresses itself best in art and poetry.

No wonder, then, that the counter-revolution cannot stand this art, and strives hard to silence it. Yet, and as Ibrahim says in his masterpiece, “Today, I saw,” their efforts will not succeed.

Today, I saw the picture from outside

and said, even now, Al-Hussein will die again.

Today, I saw what the revolutionary sees

Al-Hussein’s body trampled by soldiers’ feet,

jabbed by soldiers’ clubs.

People standing about weeping,

instead of fending them off.

The flag is a sieve of bullet holes, shredded by bayonets.

The road draped in blood.

Today, I saw blood on the soldiers’ holsters

and knew that Al-Hussein is us all,

and the more they kill him, the more he lives.

(Mustafa Ibrahim’s poetry translator: Nadia Benabid)