Last semester, spring 2017, I taught a class at Harvard on Arabic paleography and archival skills. Each week, we’d read a couple of Arabic, hand-written archival documents that I had culled from the Egyptian National Archives. The documents were mostly from the 19th century, although some dated from the 16th and 17th centuries. I’d have the documents transcribed and the quaint and odd words explained in advance. On their part, the students were supposed to a. translate the document, and b. practice reading it at home and be prepared to read it in class from the original, hand-written text.

The documents ranged from administrative correspondence to police and court records of criminal cases.

It was one of the better courses I have ever taught, and I, for one, had a blast with these excellent students. In the final week, I asked them if they would like to write something creative, e.g. a play or a short story, using one of the documents we’d read throughout the semester. This was a completely voluntary exercise that had no bearing whatsoever on their final grades. Five of the eight students responded, and I took their permission to publish their “reading” here, together with a short bio (written by each author).

Below is the second of these pieces. It is a report from the Cairo police dated March 2, 1864.

The original document comes first, followed by a transcription, then a translation, a short bio of the student, and finally, the icing on the cake: the student’s own “reading” of the document.

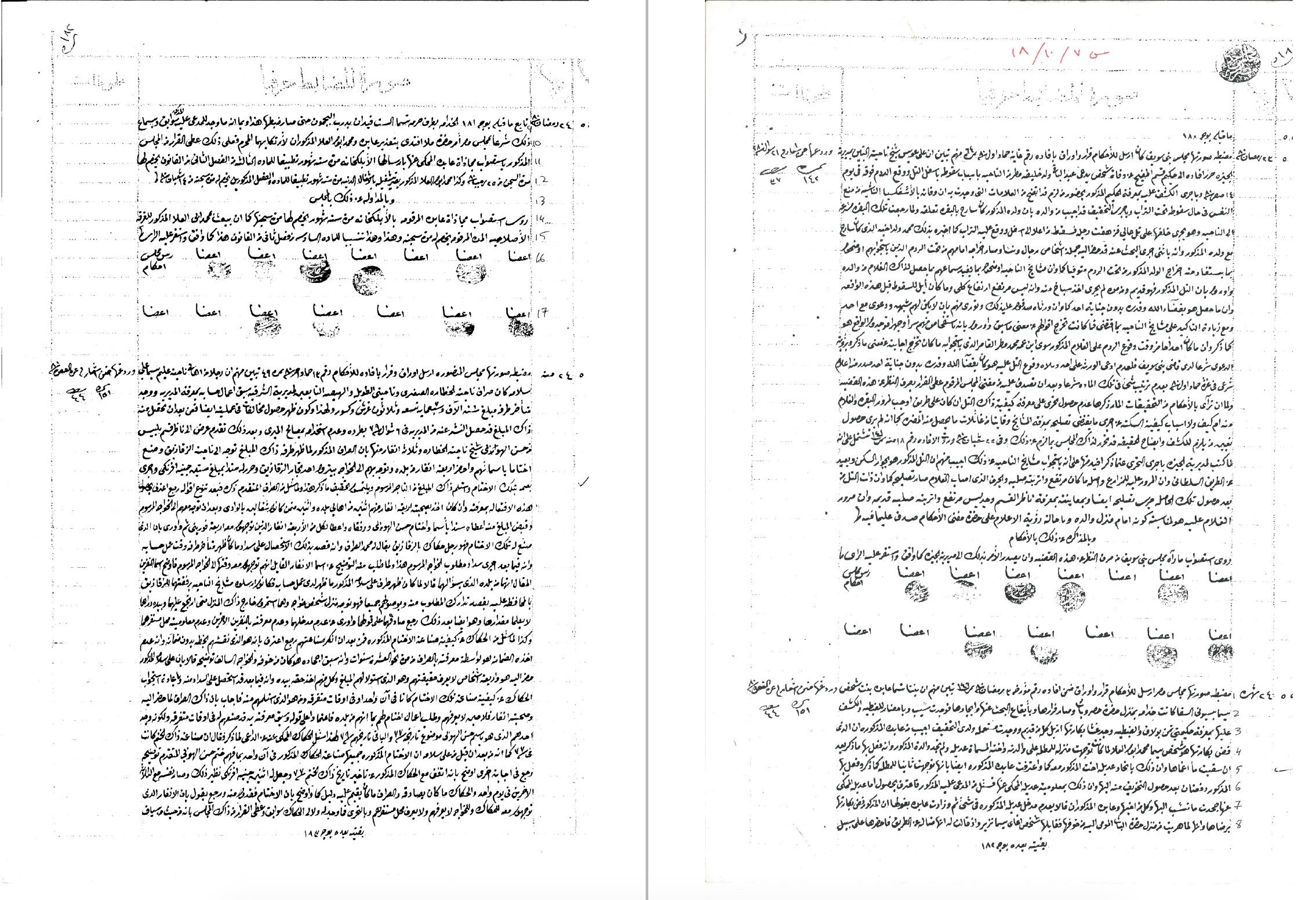

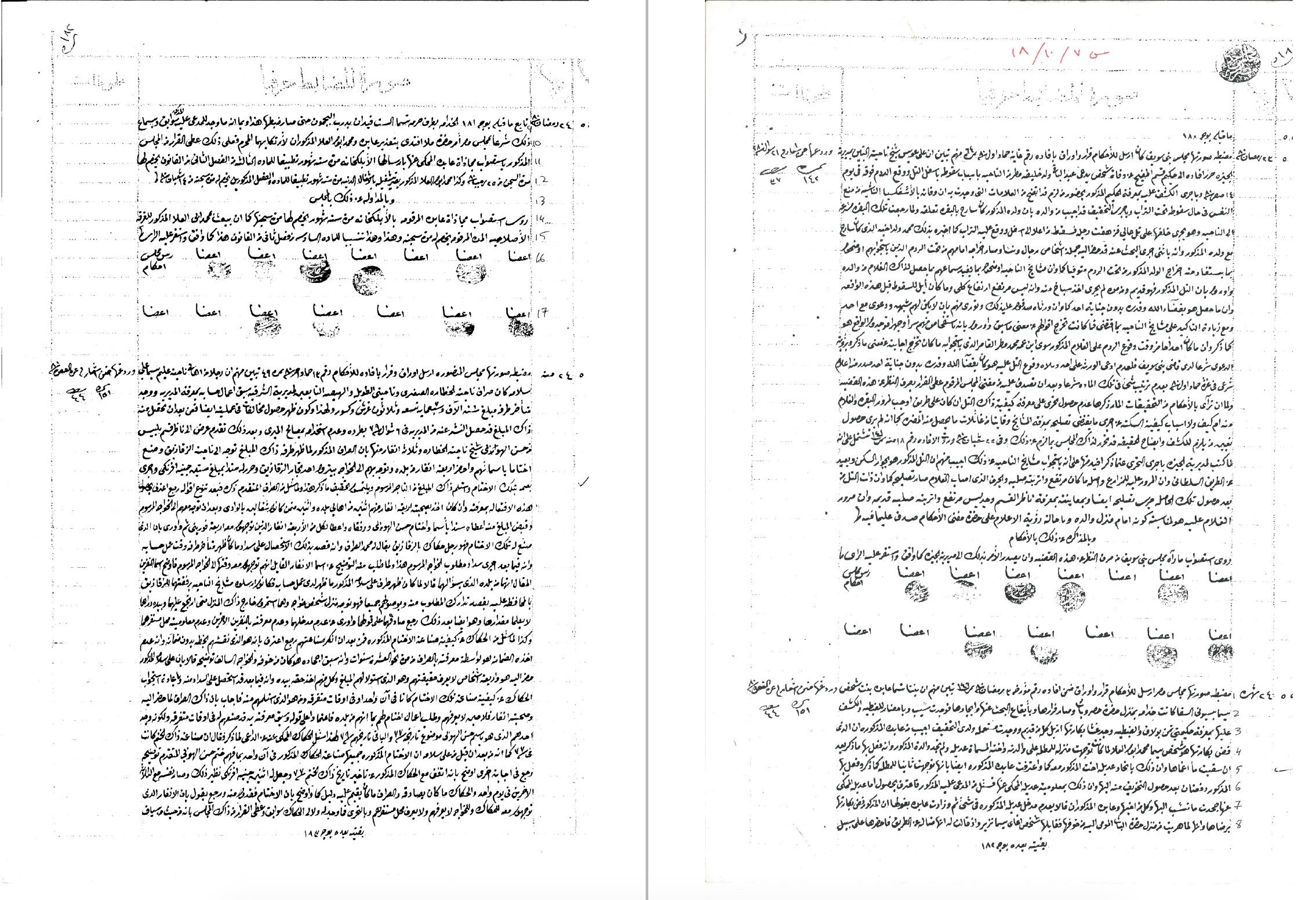

I. Original:

II. Transcription:

١. مضبطة صورتها مجلس مصر أرسل للأحكام قرار وأوراق ضمن إفادة رقم مؤرخة ٣ رمضان سنة ٨٠ نمرة ١٤٦ تبين منهم أن بنتا تسما عابدة بنت شخص

٢. يسما بسيوني السقا كانت خدامة بمنزل حضرة حصرو باشا وصار فرارها وبإيقاع البحث عنها وإيجادها فوجدت سيب وبإحضار للضبطية والكشف

٣. عليها بمعرفة حكيمتي ثمن بولاق والضبطية وجد غشا بكارتها أزيل كله من قديم ووجدت مستعملة ولدى التحقيق أجيب من عابدة المذكورة أن الذي

٤. فض بكارتها هو شخص يسما محمد أبو العلا لما كانت توجهت منزله للمطلة على والدته وأخته المسماة عديلة ولم تجد والدة المذكور وأنه فعل بها ما ذكر بعد

٥. أن سقيت ماء أغماها وأن ذلك باتحاد عديلة أخت المذكور معه كما واعترفت عابدة المذكورة أيضا بأنها توجهت ثانيا للمطلة كما ذكر وفعل بها

٦. المذكور دفعتان بعد حصول التخويف منه إليها وأن ذلك بمعلومية عديلة المحكي عنها فسئل من المدعى عليه المذكور فاعترف بحصول أما عديلة المحكي

٧. عنها جحدت ما نسب إليها وكل من أخيها وعابدة المذكوران قالا بعدم مدخل عديلة المذكورة في شيء ثم زادت عابدة بقولها أن المذكور فض بكارتها

٨. برضاها وأنها لما هربت من منزل حضرة الباشا المومي إليه من خوفها فقابلها شخص أغاى يسمى نزير وإذ قالت له أنها ضالة عن الطريق فأحضرها على سبيل

٩. تابع ما قبله بوجه ١٨١ الخدامة بطرف حرمة تسما الست فيدان بدرب البجمون حتى صار ضبطها هذا وبما أن ما وجد للمدعى عليه المذكور سوابق وبسماع

١٠ ذلك شرعا بمجلس مصر أمر حضرة ملا أفندي بتعزير عابدة ومحمد أبو العلا المذكوران لارتكابهما المحرم فعلى ذلك عطي القرار من المجلس

١١. المذكور باستصواب مجازاة عابدة المحكي عنها بإرسالها الإبلكخانة مدة ستة شهور تطبيقا للمادة الثالثة من الفصل الثاني من القانون يخصم لها

١٢. مدة السجن من ٢٥ رجب سنة ٨٠ وكذا محمد أبو العلا يصير تشغيله بالأشغال الدنية مدة ستة شهور تطبيقا للمادة والفصل المذكورين يخصم له مدة سجنه من ١٤ شعبان سنة ٨٠

١٣. وبالمداولة عن ذلك بالمجلس

١٤. روي استصواب مجازاة عابدة المذكورة بالإبلكخانة مدة ستة شهور يخصم لها مدة سجنها كما أن يبعث بمحمد أبي العلا المذكور للفرقة

١٥. الإصلاحية المدة المرقومة يخصم له مدة سجنه وهذا وهذا تنسيبا للمادة السادسة من فصل ثاني من القانون وهذا كما وافق واستقر عليه الرأي.

١٦ و١٧. أعضا

III. Translation:

- (1) Copy of proceedings of the Cairo Council. The judges dispatched a verdict and documentation containing testimony dated 3 Ramadan, ’80, #146, in which it was explained that a girl named ‘Abida, the daughter of someone (2) named Bassiouny al-Saqa, was a servant in the household of His Highness Hüsrev Pasha and escaped. When she was searched for and found, it was discovered that she was no longer a virgin. When she was brought to the police station and examined (3) by the two female doctors of Bulaq Quarter & the police department, her hymen was found to have been long ago broken, and she was found to be “used goods.” In the report, the aforementioned ‘Abida replied that the one who (4) had broken her hymen was someone named Muhammad Abu al-‘Ala, [and that it occurred] when she had gone to his house to look after his mother and sister, named ‘Adila. Yet she did not find the mother of the aforementioned, and [instead] he did to her what has been been stated after (5) she was given water to drink and fainted. This happened with the collusion of ‘Adila, the sister of the aforementioned, with him. ‘Abida the aforementioned also admitted that she had gone again to see them as stated, and the aforementioned (6) did the deed twice after scaring her, all with the knowledge of ‘Adila. The defendant was questioned and admitted it. As for ‘Adila, (7) she contested that with which she was charged, and both her brother and ‘Abida said that ‘Adila had nothing to do with it.

Then, ‘Adila added to her statement that the aforementioned had broken her hymen (8) by her consent, and that when she escaped from the household of the esteemed pasha out of fear, she met an agha named Nazir and told him that she had lost her way. So he brought the servant girl in the same manner as previously described in #181 (?) (9) to a woman named Mrs. Fidan in Darb al-Bagmun, until this arrest.

Since the defendant did not have any prior offenses, and upon it being heard (10) legally before the Cairo Council, His Honor Mulla Efendi ordered the discretionary punishment (ta’zir) of ‘Abida and Muhammad Abu al-‘Ala the aforementioned for committing the forbidden. In addition, the verdict was handed down by the aforementioned Council (11) to approve the punishment (majazat) of ‘Abida the aforementioned by sending her to the women’s prison for a period of six months in accordance with Article 3, Section II of the law, (12) minus the time already spent in jail, starting from 25 Rajab, ’80. In addition, Muhammad Abu al-‘Ala was made to perform menial labor for a period of 6 months according to the aforementioned article and section, minus time already spent in jail, from 14 Sha’ban ’80.

- Upon deliberation in the Council, (14) it was seen fit to punish ‘Abida the aforementioned in the women’s prison for 6 months minus the period of her imprisonment. Likewise, Muhammad Abu al-‘Ala was sent to the workhouse

- For the period stated, minus the term of his imprisonment, and this in accordance with Article 6, Section 2 of the law. This is what was agreed upon.

(N.B. Translation by Chloe Bordewich)

IV. Chloe Bordewich’s “reading”:

Chloe Bordewich recently finished her 2nd year of the PhD program in History & Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard, where she studies late 19th and 20th century Egypt. She enrolled in the course to prepare for dissertation research in the Egyptian National Archives.

‘Abida

An archival drama

Characters:

‘Abida, a girl, 19 years old, unmarried, daughter of Bassiouny the water carrier and servant of Hüsrev Pasha

‘Adila, a female friend of ‘Abida, about the same age, also unmarried, lives with her mother and brother Muhammad

Muhammad, 22 years old, ‘Abida’s paramour and ‘Adila’s brother, works odd jobs as a day laborer

Nazir Agha, a neighborhood patrolman

First Hakima, female doctor trained at Mehmet ‘Ali’s school, late 30s, experienced in her job

Second Hakima, female doctor trained at Mehmet ‘Ali’s school, 20 years old, recently graduated

Mulla Efendi, judge in the employ of Majlis Misr, the Cairo judicial council

Magistrates of Majlis Misr

A weasel.

Setting:

January – February 1864 (Rajab-Ramadan 1280). Boulaq, Cairo.

Scene 1

Early January 1864. Nearly midnight, a dark street in Boulaq, Cairo. The air is chilly and the road deserted. ‘Abida, a 19-year-old servant of Hüsrev Pasha, is carrying a small bundle. She approaches the door of a modest house. It is the home of ‘Adila, her brother Muhammad, and their mother.

‘Abida knocks softly at the door.

‘Abida: [hisses] Hey!

‘Adila opens the door and leans out, without stepping onto the stoop. She has been sleeping, and is groggy and confused.

‘Adila: ‘Abida! What are you doing here?

‘Abida: Let me in! I’m running away.

‘Adila: Are you crazy?! No way, not tonight. I can’t.

‘Abida: [Her whisper becomes more urgent.] Where else will I go?!

‘Adila: Why in the middle of the night? I’m confused.

‘Abida: Hüsrev Pasha knows about Muhammad and me. One of the other servants told me this morning. I’m afraid of what he’ll do to me. You know what he’s like.

‘Adila looks worriedly inside the house.

‘Abida: [reluctantly] Please, I’m scared.

‘Adila doesn’t respond.

‘Abida: [Trying a different tactic, tugs at ‘Adila’s sleeve] Wake up Muhammad. We’ll run away together! No one will know you helped.

‘Adila: [again looking inside, growing more agitated] Tonight it’s not possible! Listen. You’ll be all right for a few days; come back on Tuesday? [Pauses] Look, why don’t you go to your father? You don’t have to tell him the truth. Say you were fired.

‘Abida: You know he’s a water carrier. He has nothing.

She pauses waiting for assent, but ‘Adila seems more eager to go to sleep.

‘Abida: You’re my friend. I’ve trusted you with our secret. Muhammad and I will be together and you and I will be sisters. Isn’t this what you want, too?

Speaking breathlessly now…

How can you send me away!?

‘Adila: Enough of this, ‘Abida. I’ll tell Muhammad to be ready on Tuesday.

‘Adila shuts the door, firmly this time. ‘Abida is silent for a moment, searching the darkness for an answer. Then, suddenly, she is hit with a catastrophic thought.

‘Abida: No. No. …Is there another woman? Some girl who’s richer and prettier? A virgin? No. I’ve risked everything for him. It’s impossible… isn’t it?

‘Abida lingers on the stoop, her hand on the door, as if debating whether to knock again. Finally she turns away.

Scene 2

Streets of Boulaq, perhaps half an hour later. ‘Abida is alone now. She has wandered quite some distance from ‘Adila’s house.

A horse approaches in the darkness. Sound of a man dismounting nearby. Nazir Agha, a neighborhood patrolman, quickly crosses the mud street to ‘Abida. His sword flashes in the moonlight. He clears his throat loudly.

Nazir Agha: Who’s there?!

‘Abida is silent. Nazir Agha draws closer.

Nazir Agha: Who are you?

‘Abida: ‘Abida.

Nazir Agha: [a bit imperiously] I see. Your other names?

‘Abida: ‘Abida bint Bassiouny al-Saqa.

Nazir Agha: I see. [He doesn’t recognize the name.] It’s very late. Why are you out alone?

‘Abida: I’m lost.

Nazir Agha: Hmmm.

Suffering from poor eyesight, especially in the darkness, Nazir Agha squints as he sizes her up, trying to determine if he knows her from the neighborhood.

Nazir Agha: Are you married?

‘Abida: No, I’m just lost —

Nazir Agha: You’re a prostitute, aren’t you?

‘Abida: No!

Nazir Agha: [Almost conspiratorially, though ‘Abida does not reciprocate] Look, dear, I don’t care how you make your money. But you can’t very well do it here. This is a neighborhood of respectable people. Those of you who in the lowly professions must ply your trade elsewhere. May I suggest… Azbakiyya? A very seedy place. You’ll like it.

‘Abida: [Backing away quickly, incredulously] But I’m just lost — !

Nazir Agha: No, no, no – you can’t walk off. [He grabs her arm, firmly.] There’s been an outbreak of syphilis in these parts.

He pauses for dramatic effect, raising his eyebrows as if to say, “you must know how that goes.”

If you are in fact a prostitute, as I’m sure you are, it is your fault that so many of our fine young soldiers are, shall we say, not able to perform. I have to take you to the police station. The doctors there will examine you. If they find that you’re a virgin, congratulations – you can go. If not, well…

He shrugs and guides her offstage, taking his horse as he goes. ‘Abida makes a half-hearted effort to break away, but then gives in. She has nowhere else to go.

Scene 3

Boulaq police station, a few days later. The scene begins with the two female midwife-doctors, preparing to conduct a virginity test on ‘Abida, who is offstage. She had been held since her encounter with Nazir Agha at the neighborhood police station, awaiting examination and trial.

Hakima 1: More of the same today, looks like.

Hakima 2: Whores?

Hakima 1: So they say. The syphilis is bad, really bad.

She shivers slightly, as if imagining the symptoms.

Hakima 2: May God forgive them. Shame on them.

Hakima 1: Shame on them or shame on the men who pay for them? I don’t feel so sorry for the men.

She laughs, then begins to tidy the tiny examination room.

You’re young, but I’ve seen it all. I grew up poor, really poor. Didn’t you?

Hakima 2: (a bit defensively) Yeah. What are you asking?

Hakima 1: Well, then, I’m sure you understand why women do what they do, what we do.

Hakima 2: I didn’t become a whore! I chose to be virtuous, not sinful, and to be modest, not wear clothes that make people stare at the curves of my body. And I got married to a respectable husband. And I still have a little money of my own, thanks to the prince’s generosity.

[Quoting from the Qur’an, Surat al-Duha, triumphantly] “He found you poor and made you self-sufficient.”

Hakima 1: [Sighs, continuing the verse] “And as for the orphan, do not oppress her.”

You could say these women we’ve been seeing are self-sufficient.

Have a little pity. We got lucky.

Scene 4

Boulaq police station, perhaps half an hour later. The hakimas have just finished conducting ‘Abida’s virginity test and are sitting with her.

Hakima 2: So you’re a prostitute, huh?

‘Abida: [Trembling from the invasive procedure, but defiant] No, I’m not! I swear.

Hakima 2: You don’t have a hymen, and you’re not married. Our tests don’t lie. It’s clear that you’ve been used before. [Proudly now] We’re professionals, and we use the latest procedures. You wouldn’t find anything different in Paris.

‘Abida doesn’t refute the hakima’s accusation this time. She, too, knows is resigned to the test’s infallibility.

Hakima 1: [More kindly] So tell us — what happened?

‘Abida looks uncertain – are these women friends or foes?

The older hakima has a moment of recognition.

Hakima 1: Let me guess. You have a lover?

Abida nods.

Hakima 1: He’s a good guy, you wanted to marry him. You tried to run away with him —

‘Abida: Yes, yes – exactly!

Hakima 1: That isn’t going to work.

‘Abida: What do you mean?

Hakima 1: Sometime soon, maybe in a few weeks, maybe a month, the council will hear your case. You can say you’re not a prostitute, but we know you’re not a virgin, and if we know the police know. And on top of it all, you’re a runaway. Your employer has filed a claim. So what are your options?

Take some advice from me.

He drugged you.

‘Abida looks uncertain.

You know what I’m talking about. You can’t be that innocent, girl! They’ll haul in the guy. When the time comes, you explain how you went to the market or the shoeshine — or the fasakhany!!… [She chuckles at her own creativity, then grows serious.] You ran into this guy. He asked you to help him with something in his house. You thought he was a respectable man, but too late you realized he was a pervert. You were kidnapped, seduced! You got to his house and he gave you something sweet to drink – let’s say mango juice? No, no, it’s not the season. Let’s say pomegranate juice, that’s better. Delicious. But it was a little too delicious, and you passed out. You were poisoned. You don’t remember a thing!

The other hakima looks on uncomfortably and disapprovingly.

‘Abida: You think it will work?

Hakima 1: [Shrugging] It’s a common story.

Scene 5

At Majlis Misr, the judicial council of Cairo. February 10, 1864. Muhammad has also been apprehended and brought to the council along with ‘Abida. ‘Abida has been in jail 37 days, Muhammad 18. They have not seen or spoken to each other. ‘Adila is also present in the courtroom. It is now the third day of Ramadan.

The scene opens with ‘Abida about to tell her version of the story. She seems calmer than before, and confident.

Mulla Efendi: Shhh! Everyone quiet down, please. The noise level in here is deafening. We haven’t yet finished with this case!

Thank you. The identities of the defendants have been established in accordance with the law, and we have heard the accusations of His Highness Hüsrev Pasha, as well as the denial of the defendant, Muhammad Abu al-‘Ala, of his involvement with the other defendant, ‘Abida bint Bassiouny. We will now proceed to the defendants’ testimony.

He turns to ‘Abida.

Please present to this Council your account of what has transpired between you and this man, Muhammad Abu al-‘Ala.

‘Abida: My name is ‘Abida bint Bassiouny al-Saqa. I am 19 years old and I am not married. I worked for six years as a servant in the house of His Highness Hüsrev Pasha. [With emphasis] I worked very, very hard, but often beat me for no reason at all.

One day, almost the end of the month of Rajab, I went to visit my friend ‘Adila and her mother, who is a widow. I used to take them fresh, ripe mangoes sometimes, and home-cooked molokheyya from the pasha’s kitchen. But one day I went and found that their house was empty.

At least I thought it was empty! I was wrong. Instead ‘Adila’s brother answered the door. He is the man you see over there, Muhammad Abu al-‘Ala. [She does not look at him, but continues to look directly at the chief magistrate.] I was carrying a heavy basket of eggplants from the souq. I sat down for a moment to rest. At this point, ‘Adila came home and Muhammad asked her to get me a glass of water. Since my friend was there, I didn’t suspect that anything was wrong. Of course I trusted her.

But soon after I drank the water I got very tired and weak, and I had to lie down. I can’t remember anything after that.

The next thing I remember it was very late at night, and I was wandering in the street somewhere – I don’t know how far I’d gone. There was a pack of wild dogs howling nearby and I was freezing and numb, and I couldn’t find my way home.

That’s where the honorable agha found me.

I can’t really tell you what happened while I was unconscious, since I have no memory at all. But when I was examined at police station, the hakimas told me my hymen was broken and I was no longer a virgin. Of course, I was crushed.

Mulla Efendi: [To Muhammad] Do you now confess to that of which you have been accused?

Muhammad: [Pausing] I confess that I have deflowered this woman. But my sister is innocent, your honor!

‘Adila: Yes, yes, I’m innocent, your honor! She’s lying!

Mulla Efendi: What evidence do you have to prove your innocence?

‘Adila: I will swear to God, on the Qur’an, I have nothing to do with this crime.

Muhammad: I also swear to God that ‘Adila is innocent.

Mulla Efendi: [To ‘Abida] The defendant and his sister claim your testimony is not true – at least part of it. What do you have to say? Will you swear to God, on the Holy Qur’an, that you have told the truth in accusing this woman of collusion?

There is a long pause. ‘Abida scans the room. She doesn’t recognize anyone but ‘Adila and Muhammad.

‘Abida: Maybe – I guess – ‘Adila is innocent?

She offers an unconvincing shrug.

The magistrates converse for a moment, and those present in the courtroom begin to chatter. Then Mulla Efendi clears his throat and brings the chamber back to relative quiet (a low hum).

Mulla Efendi: Having heard the accounts given by both parties this morning, and in view of the discrepancies between the accounts, notably the confession just made by the accused, Muhammad Abu al-‘Ala, which is an emendation to his earlier denial of involvement with this woman, ‘Abida, as well as the reversal of her accusation of ‘Adila’s collusion in the matter, and moreover noting that our colleagues have grown restless from hunger, we have decided to adjourn until after iftar. We will then sentence the defendants.

Mulla Efendi gets up and shuffles out, followed by the other magistrates. A police officer comes to take ‘Abida (and another comes for Muhammad), but before they can leave the room, ‘Adila pushes toward her.

‘Adila: [A low hiss, more desperate than malicious] Why did you do that?!

Scene 6

The magistrates of Majlis Misr have become exhausted from the grueling heat and postponed the sentencing until evening, after they have broken their fast. ‘Abida is alone, back in her cell. There are no other prisoners today. It is after dark, but no one has come yet to take ‘Abida back to the courtroom.

The scene begins with an extended silence. ‘Abida is crouching in the corner, her chin in her hands.

Suddenly, a glimmer of light appears in a crack in the opposite wall of the cell. About eye-level, it catches ‘Abida’s attention. A tiny nose and whiskers appear next, then the full body of the weasel. The weasel’s slender body slips from the crack and slides across the floor of the cell. ‘Abida’s eyes follow it, and she begins to speak.

‘Abida: Hey, what am I worth?

Silence from the weasel.

‘Abida: Why don’t you answer me? What’s wrong with you?

Silence.

‘Abida: What’s the price of my hymen?

The weasel has twisted itself around in the opposite corner, so that it is facing ‘Abida. Still silence.

‘Abida: Would you pay it if you could?

Now it’s clear she’s talking to Muhammad, not the weasel. The weasel slithers out through another pea-sized hole in the wall.

‘Abida: I know you can’t. You would have married me if you could. Right?

I couldn’t look at you this morning. Or at ‘Adila. She was my friend, but she betrayed me first. She turned me out on the street. Did you even know I was at the door? Did she ever tell you I was coming back on Tuesday?

She pauses again to think, running through the events of the morning in her mind.

I don’t have a cent, you don’t have more than a few. But we had each other, and that was nice. We could’ve been happy together, don’t you think? Is it still possible?

You can marry someone else. I have more to lose.

Oh, I don’t know what will happen tonight or tomorrow or where I will sleep, or if I’ll see my father again. I don’t even know if I’ll see you again. Where will I go while you’re in jail? Will you forget me?… Will I forget you?

She hugs her legs to her chest and shivers.

Is there already someone else? I thought so, but then… you confessed. Why did you confess, when you knew I lied?

Did I ruin your life or did you ruin mine?

She puts her head in her hands.

Scene 7

Later than evening. ‘Abida is back before the magistrates of the Majlis, awaiting her sentencing. Muhammad is brought out separately.

Mulla Efendi: We have reviewed the facts of the case and are prepared to sentence the defendants.

‘Abida: [Boldly] I want to say something first. [Pause] Your Honor.

Mulla Efendi: Yes? Go ahead.

‘Abida: That man did not drug me. What happened between us was my choice.

The magistrates look startled.

‘Abida: [Gaining confidence] I went to his house on purpose and agreed to it…

Mulla Efendi: This is a highly unexpected confession. Do you understand that you have confessed your own collusion in the crime of your deflowering? That you consented, willingly, to the forbidden?

‘Abida: Yes, your honor. I do.

The magistrates again confer among themselves.

‘Abida: Excuse me. One more thing, your honor. I went there twice!

The magistrates appear even more shocked and appalled.

Mulla Efendi: In that case, you will be both be sentenced according to the proper provisions of the Sultanic Code.

For the first time, ‘Abida steals a glance at Muhammad. Neither she nor we can read his expression, and she doesn’t succeed in catching his eye.

Mulla Efendi: After deliberation, the Cairo Council hereby sentences you, Abida bint Bassiouny al-Saqa, to six months’ imprisonment and labor in the spinning factory, minus the 37 days you have already served in jail while awaiting this hearing, as stipulated in Article 3, Section II of the Sultanic Code. Muhammad Abu al-‘Ala, the Cairo Council hereby sentences you to six months of hard labor at the Boulaq iron foundry, minus the 18 days you have already served while awaiting the hearing.

With this, I declare the case closed.

With this abrupt ending, the officers of the council, the scribes, the onlookers, etc. begin milling around, conversing. ‘Abida is left on one side of the room, Muhammad on the other. Again we can’t see Muhammad’s face; it is obscured by a small crowd. ‘Abida cranes her neck to see him, to see whether he is looking back. She can’t tell. An officer comes to take her first, and walks her past Muhammad on their way out.

‘Abida: Do you still want me?

He turns to her to call out, but she has already been pushed forward, out of the courtroom.

Summary of Scenes:

Scene 1:

In this scene, ‘Abida has decided to leave Hüsrev Pasha’s service and hopes to run away with Muhammad, with whom she has had a couple of intimate encounters. ‘Abida has been told by a fellow servant that her employer has learned of the illicit relationship, and she has fled in fear of punishment. ‘Adila, Muhammad’s sister, is a friend.

‘Adila answers the door, but tells ‘Abida she can’t come in this time. She should come back in a few days. ‘Abida pleads with her — she cannot go back. ‘Abida insists that ‘Adila bring Muhammad to the door, reminding her of the details of the relationship and Muhammad’s affection for her, but ‘Adila cannot or does not bring him.

‘Abida pleads with ‘Adila. Should she try to return to Hüsrev Pasha’s house, risking violent punishment? Should she return to ‘Adila’s and demand to be let in? ‘Adila’s unexpected refusal has upset her – ‘Adila has known of ‘Abida’s relationship with Muhammad and helped them find time alone together. It is enough to sow doubt. Is Muhammad with another woman? Has his mother, the widow, planned to have him engaged to someone else?

‘Abida is poor, a woman, and now a woman without work or a home. What options does she have? This scene captures the decision-making process of someone without choices.

‘Adila squeezes the door shut, apologetically but firmly.

Scene 2:

Nazir Agha, a neighborhood patrolman, asks ‘Abida what she is doing out at night alone and whether she is married, and she tells him she is from a different area and is lost (not wanting him to return her to Hüsrev Pasha). He doesn’t buy it. Only prostitutes, he tells her, wander the streets of Boulaq at this hour. Prostitution isn’t illegal, but there has been a recent outbreak of syphilis in the neighborhood brothels, which has been of great concern to the local notables. Nazir and the other aghas have been trying to round up the prostitutes responsible for spreading the disease. ‘Abida will need to be examined by the hakimas at the police station.

Scene 3:

This scene is a dialogue between the two hakimas, who are discussing their attitudes toward their work and their conjectures about the woman they’re about to examine. They are women from marginal backgrounds who have gained a measure of authority thanks to the state. They work out of the police station, and one of their primary responsibilities is conducting virginity tests in court cases pertaining to lost virginity.

One of the hakimas is a little older and more experienced. She has seen a million similar cases. She sees something of herself in the younger women on whom she conducts the invasive tests; she, too, came from a poor background, was a ward of the state. The other hakima is newly graduated. She is anxious about morality and what ‘Abida might have done to bring this misfortune on herself. At the same time, she is very proud of the state-of-the-art medical knowledge she has acquired at the women’s medical school. She wants to do things correctly – scientifically and morally.

The key issue in this scene and the next is the complex relationships among women of low status, the effect of the power differential created by the state’s professionalization of female forensic doctors, and, more broadly, why women blame other women for situations they themselves feel powerless to change.

Scene 4:

‘Abida is found to be, in the court’s later words, “used goods.” No one doubts the soundness of the medical procedure used to search for her intact hymen, so there is no use disputing the findings. ‘Abida had entered the examination room resignedly; she knew this was what they would find. Now she asks the hakimas what her future will look like.

The conversation is primarily with the older hakima. The younger, more judgmental one thinks women like ‘Abida have given all women a bad name. (Imagine a woman blaming another for inviting sexual harassment with tight pants or a flirtatious glance.) But the older one decides to give her some advice for her appearance before Majlis Misr, the judicial council that will decide her punishment. She helps her craft the story that ‘Abida will later tell in her first court appearance – that Muhammad drugged her before their encounter. Claiming drugging, and thus unconsciousness, the hakima assures her, will diminish her responsibility and place the blame more squarely on Muhammad. This has worked many times before – a common story, yet often accepted.

Scene 5:

We do not witness the entire scene. Muhammad is silent; we do not hear his initial testimony. ‘Abida comes forth and tells the story she has crafted with the help of the hakima. But she keeps glancing at Muhammad and at ‘Adila, who is also present with her brother. Feeling angry at her friend ‘Adila for refusing her at the door the night of her escape, she adds at the end of the story a detail about ‘Adila’s collusion with Muhammad in drugging her. But when both Muhammad and ‘Adila insist that ‘Adila was never involved, ‘Abida readily confesses that it’s not true. She has moments of confidence and self-assuredness, and moments of seeming overwhelmed, unsure. At these moments, her eyes dart around the room, looking for friends.

There is a break in the proceedings and ‘Adila brushes past ‘Abida. “Why did you do that?” she hisses, more distraught for her brother than malicious.

The court adjourns until evening.

Scene 6:

A sudden pang of guilt comes over ‘Abida. Muhammad surely will be sent to hard labor; he cannot afford to pay the price of her hymen. Would he pay if he could? She attempts a thumbnail calculation of her hymen’s worth, but she is not sure – nor is she sure how much money Muhammad has. Does he want to marry her or not, anyway? Is there any hope of it happening? Has she ruined his life, or has he ruined hers?

‘Abida is scared and she lacks information, but she is not stupid. Has she done the right thing? When the scene closes, we don’t know what kind of conclusion ‘Abida has reached.

This monologue should be a dramatic crescendo, focusing intently on the interior life of someone with a precarious existence.

Scene 7:

Before anything else happens, ‘Abida blurts out that Muhammad never drugged her; she went to his house willingly, knowing what would happen. There is a long pause while those present calibrate their responses. This woman has just confessed her own collusion in the crime of her deflowering.

Mulla Efendi reads the sentences: 6 months in the women’s prison for ‘Abida and 6 months’ hard labor in the workhouse for Muhammad.

The final moment before the curtain closes is a momentary exchange between ‘Abida and Muhammad. She has stolen several glances at him during the sentencing, hoping for a hint of his feelings. We can’t quite read him, so we feel uncertainty along with ‘Abida. Has her honesty done her any good? Her final words to him as they are led out of the room (and back to jail) are something like “Do you still want me?” ‘Abida never hears his reply.

We are left feeling that ‘Abida’s future is uncertain – perhaps they will end up together after their 6 months, or perhaps they will never see each other again. She cannot count on anything; her life, and her decisions, are a gamble.

[…] from the Egyptian archives, and the assignment was to write a play based on one of these files. (The full play is here.) I chose the story of a 19-year-old servant, ‘Abida, the daughter of a water carrier, who was […]

[…] ال كانوا بيكشفوا عليهم. لكن شجعت واحدة من طالباتي إنها تكتب عمل أدبي (مسرحية قصيرة) بناء على وقائع قضية من القضايا دي ال كنا […]