Published in Mada Masr on 21 December 2019

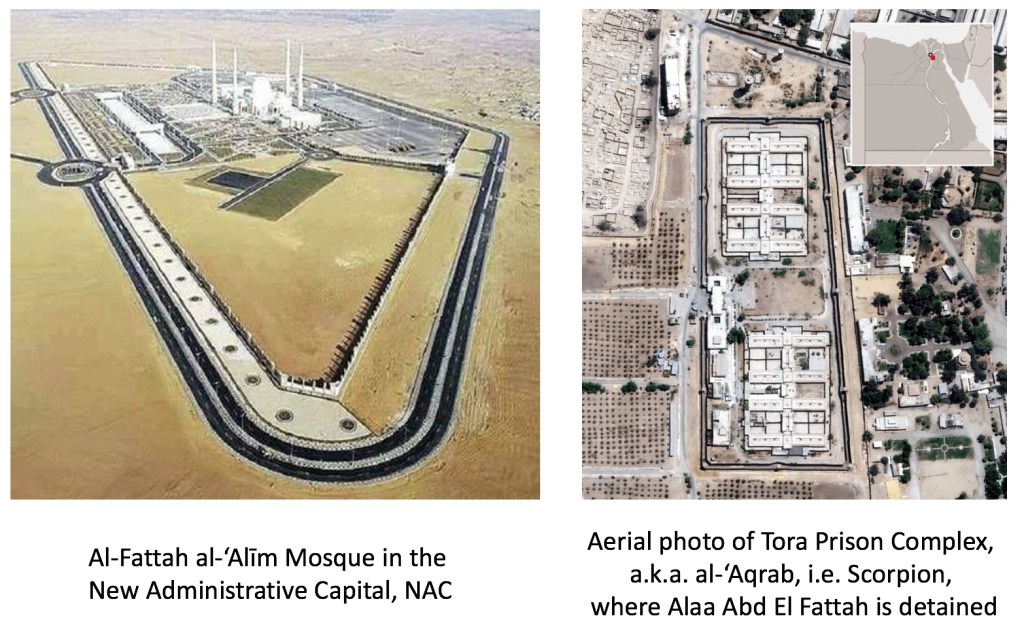

Software developer and activist Alaa Abd El Fattah has been imprisoned in the Maximum Security Wing 2 of the Tora Prison Complex for the last three months. He was arrested by national security agents on the morning of September 29 as he was leaving Dokki Police Station where he had been forced to spend 12 hours every night — from 6 pm to 6 am — as part of his probation since his release from prison at the end of March after serving a five-year sentence.

Alaa is being held in remand detention on charges of belonging to an illegal organization and spreading false information. His detention is renewed by the State Security Prosecution every 15 days.

The conditions of Alaa’s current imprisonment are the worst of his multiple detentions dating back to 2006. He has no access to reading materials, sunlight, or clean water. All visitations are conducted through a glass barrier and he has no physical contact with his family.

At his most recent detention renewal hearing on December 9, Alaa addressed State Security Prosecution and spoke out about the conditions of his detention. In his remarks, he made historical references to the Egyptian state’s ascent to modernity and its relation to the written word.

Mada Masr asked historian Khaled Fahmy, a professor of modern Arabic studies at Cambridge University and the author of four books on the social and cultural history of nineteenth-century Egypt, to critically engage and reflect on Alaa’s remarks.

The following are Alaa’s remarks in full followed by Khaled Fahmy’s text.

*********

The State Security Prosecution denies lawyers access to transcripts from its detention renewal hearings. As such, extracts of Alaa’s remarks were reproduced by his lawyers and family who attended the hearing. The prosecutor asked Alaa if he had any complaints to put forward. This was his response.

My complaint concerns the conditions at the Maximum Security Prison 2 at Tora and the violation of my rights as stipulated in the prison bylaws. Chief among these rights is the protection of our health in the winter. I am still deprived of two hours of daily exercise and I never get any exposure to the sun. I am also deprived of hot water or any heating device for showering. We sleep on a concrete bench without any insulation and the prison administration has not provided us with mattresses or standard-issue pillows. The cold seeps into our bones.

Yet the most important issue for me is the denial of the written word. I am not allowed any books or magazines, and I am denied the right to subscribe to newspapers or have access to the prison library. For the past two months and 10 days, I have repeated my complaints. My family has put forward countless petitions to various authorities tasked with prison oversight and with monitoring the performance of the Interior Ministry.

Today, I realize the issue goes beyond the denial of my rights as a security measure; rather, it exposes a phobia and a hatred of the written word itself. Sadly, this phobia has captured the mindset of the Egyptian state and has spread throughout it.

I see no logic or reason for my imprisonment other than the written word, especially since my arrest came alongside that of distinguished academics and researchers, and was a precedent for the arrest of professional journalists.

The hold that this hatred for the written word has over state institutions, be they decision-makers or security agencies, is strange. The first godparents of Egyptian culture, such as Rifa’a al-Tahtawi, helped to develop curricula and translations for military schools as part of the effort to guide Egyptian culture towards modernity.

Until not so long ago, it was logical to expect that those appointed to state institutions meet certain criteria that included competence, awareness, cultural depth, and a capacity for expression. In many advanced countries, state institutions include experts and scholars of various sciences. They tend to have practical expertise and theoretical knowledge in strategic fields which allows them to analyze situations and relationships, enabling them to make decisions. There are even experts in environmental sciences and natural resource management in the ranks of the military leadership, and experts in social sciences and the human psyche within the police.

For a long time, this was also the case here. But suddenly, the state became antagonistic to this status quo and it is now attempting to fill its ranks with clones who do not think, and who are unable to engage in debate or conversation. This is extremely harmful to society at its very core. Because, whether we like it or not, the authorities that manage this society currently embody the collective mind that is making decisions and determining fates. If this mind is blocked from thinking, from the written word, and from the ability to stir knowledge and debate, it will surely be reflected on society as a whole and will lead to serious damage.

What we need now is to stand by the right to know, to exchange information, to freely express our views without fear. This will not only benefit prisoners, but society as a whole.

When I demand my right to read and write, I am not asking for a luxury. I demand to live in this time, in this century, and to be allowed to preserve my ability to contribute to the continuation of Egypt’s struggling renaissance project.

If the prosecution succeeds in empowering me with this demand, it will stand as a victory, not for me, but for the written word. We need to restore the importance of words and the right to the written word; they do not represent a threat to society but rather are a necessary part of its development and progress.

*********

Thinking with Alaa

By Khaled Fahmy

In his most recent appearance in front of the State Security Prosecutor on December 9, Alaa Abd El Fattah was asked if he had any complaints of the conditions of his incarceration, to which he answered that he had two.

The first was serious health violations including being deprived of his two hours of daily exercise and of exposure to the sun.

The second was being denied access to books, magazines, newspapers and the prison library, which he attributed to what he called a state “phobia and hatred of the written word.”

This phobia, Alaa argued, is a new twist in the history of the Egyptian state.

“The first godparents of Egyptian culture, such as Rifa’a al-Tahtawi,helped to develop curricula and translations for military schools as part of the effort to guide Egyptian culture towards modernity. Until not so long ago, it was logical to expect that those appointed to state institutions meet certain criteria that included competence, awareness, cultural depth, and a capacity for expression … But suddenly, the state became antagonistic to this status quo and it is now attempting to fill its ranks with clones who do not think, and who are unable to engage in debate or conversation. This is extremely harmful to society at its very core.”

I found this recourse to history fascinating, for I would have expected Alaa, with his characteristic insistence on the law and human rights, to stress the illegality of his situation and to argue how his current predicament contravenes not only international standards or human rights principles, but the very text of the Egyptian Constitution and many pertinent laws.

I expected Alaa to refer to Article 55 of the Constitution which states that prisoners “may not be tortured, intimidated, coerced, or physically or morally harmed” and that “violating any of the aforementioned is a crime punishable by law.” I also expected him to refer to Law 23 of 1973 that added an article to the Prisons Law (Law 386 of 1956) that stipulated that each prison should have a library containing religious, scientific, and cultural books for prisoners to consult during their free time. “Prisoners,” the law adds, “are allowed to receive books, newspapers and magazines at their expense, according to the internal bylaws of the prison.”

But Alaa referred to none of these legal statutes that he is certainly familiar with. Instead, he resorted to history, a tactic with which I agreed, but one which also raised some questions in my mind.

I have always believed that looking into the history of the Egyptian state can illuminate much of what otherwise may appear to be illogical, counter-intuitive or even counterproductive behavior on its part. For many years now, I have been poring over the state’s own archives, especially the archives of the two institutions that represent its essentially coercive nature — the army and the police — to uncover its inner logic, gain an understanding of how it functions, and get an insight into how it views itself. Given this exposure to state archives, I found myself sharing with Alaa his puzzlement and bewilderment at how the state treats its prisoners, but I also found myself disagreeing with some of his assumptions about the origins of this draconian regime that hovers above all of us like a dark ominous cloud.

For the Egyptian state in 2019 to deprive its prisoners of health and knowledge is not only a violation of its own laws, but a reversal of a long historical trajectory in which it occasionally prides itself. Some would like to view this trajectory as starting with the story of Joseph in Pharaoh’s prison, but this would be as ludicrous as arguing that Sisi’s suppression of the Muslim Brotherhood is akin to Ahmose’s expulsion of the Hyksos, a comparison that the fanatic supporters of the state are wont on repeating.

The present Egyptian state, with the army and the police at its very core, is no more than 200 years old. It came into being when Mehmed Ali Pasha introduced conscription as a way to raise an army with which to fight his dynastic wars and to entrench himself and his family firmly in Egypt. Once this momentous decision was taken, Egypt’s manpower assumed singular importance. The Pasha and his assistants became acutely concerned about the available manpower and how it may not be large enough to till the soil, the ultimate source of wealth, and to carry arms to defend the new realm. The beginning of Egypt’s health system is intimately linked to the army, and it is no wonder that the jewel in the crown of this health system, the Qaṣr al-‘Ainī Hospital, which was founded in 1827, was a military hospital whose primary task was to cater to the soldiers of the newly founded army. All the subsequent medical and public hygiene measures that were introduced in the first half of the nineteenth century, such as the collection of vital statistics, vaccinations against smallpox, opening free clinics, imposing quarantines and so forth, were measures introduced by Mehmed Ali and his assistants — i.e. the state — to protect the country’s manpower in order, in turn, to protect their own interests.

This cynical and sinister concern with health matters was most evident inside prisons. Throughout the middle decades of the nineteenth century — from the late 1830s to the late 1870s — one notices a clear shift in the state’s penal regime from relying on beating, whipping, execution and all forms of corporal punishment, to incarceration. But for incarceration to work as a deterrent, it had to be reformed so that prisons would lose their original meaning as places of banishment and exile to become places of a temporary loss of freedom. In turn, close attention had to be given to the hygienic conditions of prisons and to the health condition of prisoners. Fear of epidemics was also always there, something the authorities had previously learnt from army barracks: gather a large number of men in an enclosed space and confine their movement, and sure enough you will end up witnessing an outbreak of typhus, syphilis, scabies, or TB.

Thus, the moment the Egyptian landscape was dotted with prisons and penitentiaries was the moment we witnessed an acute concern with the health of prisoners. Clot Bey, the founder of the modern Egyptian health system, paid very close attention to the health of prisoners. He argued against shackling their hands to cell walls. He insisted that prison cells should have windows large enough for air and sunshine to get through. He was concerned with the quality of straw used for mattresses. He was also concerned with the quality of prison food and labored to come up with a balanced, healthy diet. Prisons were to be inspected for health purposes at least once a week. Prison hospitals received particular attention.

These significant inroads were not triggered by any societal pressure. They were not part of any humanitarian calls emanating from society at large. There was no public demand for the state to maintain prisoners’ health. As such, this concern with the general welfare of prisoners was not similar to what can be detected in Victorian England, where prisoners were seen as poor souls who might have erred but who should be reformed, rehabilitated and reintroduced into society as healthy, productive members. Rather, in Egypt, this was always a state concern, emanating not from society, but from the state and aimed at protecting its interests. These might be poor souls; however, they are, above all, precious manpower who have to be protected and augmented for pecuniary (taxes) and military (conscription) purposes.

When in 1830 Sultan Mahmud II gave the island of Crete to Mehmed Ali to govern as a reward for his help in subduing the Greek Revolt (1821-1830), the Pasha was very disappointed, saying that Crete was sparsely populated. A country with no people is not worth governing, he argued. And throughout his long tenure in Egypt, he was deeply concerned about how underpopulated it was, a concern that culminated in successfully carrying out a national census in 1847 — one that counted individuals, not households. This concern with the size of the population, ultimately, was what lay behind the attention given to the health of the population at large, and of prisoners in particular.

Two centuries later, the problem of population has been reversed. The Egyptian state now thinks there are too many Egyptians in Egypt. Egyptians breed too much, it argues. They are lazy and indolent, it argues. And their youth are ungrateful and unruly. This youth belong to prisons, but not to modern prisons, i.e. nineteenth-century ones with their obsessive concern with cleanliness and hygiene. Egyptians, the state now argues, are all homi sacri, expendable. They belong to dungeons where they can be incarcerated in dim, overcrowded, unhealthy cells, deprived of proper mattresses, hot water, air and sunshine.

This is what the history of the Egyptian state looks like if told from the point of view of prisoners. And this is what Alaa is pointing to.

Alaa’s second complaint is equally intriguing.

Alaa is bemoaning the fact that the state seems determined to deprive its prisoners not only of their health but also of their right to read, to be connected to the world, to live in the present. There is a phobia of the written word, he says. Those who now run state institutions “do not think, and are unable to engage in debate or conversation. This is extremely harmful to society at its very core.” This is in contrast, he says, to a moment in the past when state officials like Rifa’a al-Tahtawi met “certain criteria that included competence, awareness, cultural depth, and a capacity for expression … [There were even] experts in social sciences and the human psyche within the police.”

This is certainly true. There is an undeniable deterioration in the performance of the Egyptian state that can be detected over the past 100 years at least. If I reflect on what the most important lesson I learned after long years consulting the archives of the nineteenth-century Egyptian state, I would say it is the deep-seated self-confidence, self-respect and self-worth those who ran the state felt. And I don’t mean ministers and heads of government departments. I mean countless nameless bureaucrats and scribes who labored over their neat and tidy registers to keep the machinery of government, dulab al-‘amal al-miri, well-greased and smoothly run. My recent book, In Quest of Justice, attempts to capture this spirit of self-worth and self-respect. This stands in sharp contrast to the utter incompetence, ineptitude and corruption of present-day state agencies.

But make no mistake, this efficient, self-confident nineteenth-century bureaucracy did not aim to serve us, the people. It was also never accountable to us in any shape or form. Rather, this was an aloof, alien administration which was concerned, above all, with its own survival and its own well-being.

This self-serving attitude can best be detected in the education policies of Mehmed Ali, policies in which Tahtawi was deeply involved. Of course, we are all enamored of Tahtawi, the Azhari sheikh who extracted gold in summarizing his sojourn to Paris. We are fascinated by his illuminating career in translation, education and publication. We are all beholden to the Bulaq Press, which along with Qasr al-‘Aini Hospital, is the only institution to have survived from the great Pasha’s times, and which printed not only Tahtawi’s Parisian rihla, but also gems of Arabic classics in history, fiqh and biography. We think of Tahtawi as the father of translation, which we take to mean translation from European languages, mainly French — our conduit to modernity and enlightenment. Tahtawi is the doyen of our nahda, our prophet of modernity.

Takhlis al Ibriz fi Talkhis Bariz or The Extraction of Gold in Overviewing Paris (Cairo: Blulaq, 1834)

But Tahtawi was primarily a bureaucrat, a state official, and a very successful one at that. His rihla was not like previous rihlas of Muslims scholars seeking knowledge, even in China. Rather, he was a member of an official, state-funded student mission to Paris. Upon returning, he was employed as a translator in the newly founded military hospital, Qasr al-‘Aini, which was still located in Abu Za‘abal to the northeast of Cairo next to the military camp of Gihad Abad. His long career was that of an astute, clever government employee, who knew which way the wind was blowing, and who succeeded in defending his bureaucratic turf, extracting funds for his projects, defending his acolytes and securing government jobs for them. Above all, he learned how to navigate his way through the Egyptian bureaucracy without ruffling any feathers. He set the pattern for multitudes of Egyptian intellectuals to follow: not “publish or perish”, but “humble or perish.” Two centuries later, Farouk Hosni, the longest-serving minister of culture in modern Egyptian history, could pride himself in saying that his biggest accomplishment was to drag intellectuals back to the “barn”, by which he meant the Ministry of Culture.

As to the alleged renaissance project that Tahtawi was a part of, it was nothing of the sort. In spite of the fact that Mehmed Ali is often praised for spreading education, opening one school after the other, sending students to Europe and founding a modern press and the first regular newspaper in the East, he was adamantly opposed to spreading education to the masses. In a letter to his son, Ibrahim Pasha, he warned him of the dangers such a step would entail. He told his son to look at what had happened to European monarchs when they attempted to educate their poor. He added that he should satisfy himself with educating a limited number of people who could assume key positions in his administration and give up ideas about generalizing education. True to his word, Mehmed Ali was keen on opening “schools” that were in fact polytechnics intended to furbish the growing administration with its need for competent, self-respecting, but also docile, bureaucrats. (The Turkish word “medrese” i.e. polytechnic, that was used to refer to the Pasha’s education institutions, was confused with the Arabic word “madrasah”, which in the nineteenth century meant “primary school.” Had the Pasha intended to spread primary education to Egyptian youth, his educational institutions would have been called “mekteb”).

(Turkish original on the right, Arabic translation on the left; source: Egyptian National Archives)

The same could be said about the Bulaq Press, the Government Press, al-matabi‘ al-amiriyya, which was founded in 1821. This press certainly launched an impressive project to edit and publish gems of classical Arabic literature. But we often overlook the fact that this press was initially founded to serve the army, not to edify the reading public, and that for the first 30 years of its existence more than half its publications were military and naval books intended to be used in camps to drill soldiers and sailors on how to serve the Pasha’s mighty military machine. The editors, translators, and language correctors who labored in this gilded institution had one eye on their books and another on the great Pasha, aiming to please him. This is why the biographies they published, for example, were those of great men like Bonaparte, or great women, like Catherine the Great. When they suggested publishing a Turkish translation of Machiavelli’s The Prince, the Pasha objected saying it would be a waste of his money as the book contained nothing which he didn’t already know.

What Alaa is complaining of, therefore, is not a reversal of a once-lofty project, nor a hijacking of a noble project that Tahtawi once heralded. Rather, it is the net result of an essentially flawed enlightenment project, one which was launched by the state to serve the state. We, the people, were never the intended beneficiary of this project. Our current predicament is that whereas once we were of some value to the state, we now are a hindrance, a nuisance, and even a danger. Hence the state’s desire to build a new fortified capital to which it can withdraw so as to isolate itself from our irritating presence; and, at the same time, build dungeons into which thinking, critical and engaged citizens like Alaa can be thrown. Their confinement in these dungeons is not meant as a deterrent to other like-minded citizens, but to rob them of their health and their ability to think.

This is what Alaa is complaining of, and in so doing, he reminds us, once more, that he is the bravest, most critical, most engaged citizen of us all. At a time when Egypt has been turned a large prison, Alaa has managed to cling to his humanity and be the freest Egyptian.