N.B. This article was written in May 2011. An Arabic translation was published in Majlallat al-Dirasat al-Falastiniyya, v. 86, Spring 2011.

On January 25, I had my first encounter with tear gas. Answering many calls on Facebook and other social network media, I went to Tahrir Square to join my sister and her son who had already been there for a few hours. As soon as I entered the square I realized that something big was happening—the last time I saw such a large crowd in Tahrir was in 2003 during the demonstrations against the US invasion of Iraq. The crowd kept getting bigger and bigger until shortly after midnight when the police managed to disperse us using water cannons and firing round after round of tear gas canisters.

Three days later, on what was dubbed “The Friday of Rage”, I found myself together with tens of thousands of fellow Egyptians face to face with Mubarak’s notorious riot police on al-Galaa Bridge, then on Qasr al-Nil Bridge that leads to Tahrir Square. Determined to prevent us from retaking that most central square in the city, the police confronted us with water cannons, rubber bullets and tear gas. A few hours later, the police collapsed and the road to Tahrir Square was left wide open, inaugurating the eighteen-day sit-in that ousted Hosni Mubarak from power and ended his 30-year long reign.

During these tense hours on the bridge I had little time to reflect on what was happening, my energies being concentrated on trying to distinguish between the sound of rubber bullets and that of live ammunition, and on doing my best to avoid the tear gas canisters that were being hailed on us with rapid succession.

Later that day when I returned home, it dawned on me that what I had witnessed was an historic occasion. Needless to say, one could not predict that a fortnight later the defunct Mubarak regime would collapse, and that the Egyptian people would be charting their own future. Still, I could not help but go back to the events of that fateful day and to reflect on the irony of its date, as well as the names of the bridge and the adjacent square.

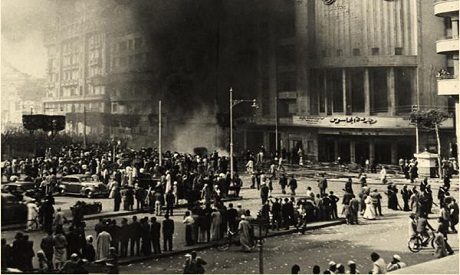

25 January has already lent itself to the name of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 that saw the downfall of one of the oldest serving Arab tyrants. Prior to the Revolution, the 25thof January was known as “Police Day”, commemorating a 1952 incident when the British army besieged the Egyptian police station in the city of Ismailia on the Suez Canal. The standoff soon turned bloody and the confrontation left more than fifty Egyptian policemen dead. When news of the massacre reached Cairo the following day, the city rose in flames and many British and European businesses were attacked. Six months later, the Free Officers staged their coup that deposed King Farouk and launched the Egyptian republic. Among many symbolic gestures that the new regime did was to declare January 25 a national holiday in honor of the heroic stance adopted by the Egyptian police against the foreign occupier.

Fifty nine years later whatever national credentials the Egyptian police might have had was completely lost. Instead, the Egyptian police became a prime tool for Mubarak to tighten his grip on society, stifle free expression, arraign and torture opposition figures (especially Islamist ones), and suppress political opposition, nipping it at the bud before it forms any serious challenge to his regime. Consequently, the Egyptian police became prime agents of repression, their stations turning into dungeons were torture was systemically practiced. It was therefore not an accident that one of the main Facebook pages urging people to take to the streets on “Police Day” was titled “We are all Khaled Said”, named after the 27-year old man from Alexandria who was beaten to death by plainclothes policemen last summer.

The new connotation of January 25 was not the only irony that crossed my mind on contemplating the momentous events of the Egyptian Revolution. The naming of al-Galaa Bridge was another one. This bridge was initially called “Kubri al-Ingiliz”, the “English Bridge”, and it acquired its new name (which translates as “Evacuation”) following the withdrawal in 1954 of the last British soldier from Egyptian soil, thus ending a 72-year long occupation. Yet it was on al-Galaa Bridge that I found myself confronting not any foreign occupation force, but the Egyptian police which was supposed to protect me and my fellow citizens.

Even the name of that now world-famous square, Tahrir, was not devoid of irony. Originally named Ismailia Square after Khedive Ismail who is credited with designing modern Cairo, the square was renamed Tahrir, i.e. Liberation, by the Free Officers regime in 1955 to commemorate the withdrawal of British troops the previous year and to signal the revolutionary regime’s pledge to help with the wider Arab anti-colonial struggle that was being waged from Algeria to Palestine. Yet, it was that same regime which instead of liberating Palestine as it promised in 1967, ended up losing the entire Sinai Peninsula (and much more) in a catastrophic defeat the likes of which has rarely been seen in modern history. Under the Sadat and Mubarak regimes, furthermore, Egyptians felt far removed from the lofty ideals espoused by that square’s name as they found themselves humiliated, downtrodden and besieged in their own homeland.

The January 25 Revolution put an end to this miserable state of affairs. The Revolution is a clear reversal of a historic trend that has shaped Egyptian history for much of the twentieth century. Whatever economic gains Egyptians accomplished over the past sixty years (and they have not been numerous) and whatever foreign policy success the Egyptian state could claim (and again, these have been few and far between) came at a huge cost. For decades, the majority of Egyptians had their human rights violated, their freedoms abrogated, their voices silenced and their bodies tortured.

The uprisings that are springing out in many Arab countries – in Libya and in Yemen, in Jordan and in Bahrain – like the revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia, are all part of an effort by Arab peoples to regain the dignity that they have been denied for decades. Ever since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire following the end of the First World War and the subsequent drawing up of the map of the region as we know it, we have seen different regimes repeatedly and systematically failing to answer the wishes and desires of their own people. In country after country, and in decade after decade, the Arab peoples have seen their liberties, their basic rights and their dignities being violated and denied, mostly at the hands of their own governments. And while the people attempted to rise up against their local tyrants, two main forces stood in their path towards liberty and dignity: Israel and oil. For in addition to the misery it inflicted on millions of Palestinians, the Zionist project also sapped the creative energies of the entire region and dragged it into the quagmire of repeated wars—wars that were cynically used by local tyrants to stifle freedoms. And the appearance of oil in such huge quantities gave local tyrants much needed breathing space and allowed them to postpone desperately needed political reforms.

The Egyptian Revolution is still young and the Arab Spring is still in its early days. The road ahead is bumpy and the path to democracy will be difficult. As we are seeing in Libya and in Yemen, local tyrants are not willing to leave without putting up a ferocious fight. The counter-revolutionary forces will stop at nothing to maintain the status quo and to stop this revolutionary trend in its tracks—witness the Saudi military support of the beleaguered Bahraini monarch. Above all, both the US and Israel will not be happy to see the collapse of the local Arab tyrants – their prime tools of establishing their respective hegemonies on the region.

Nevertheless, the path to dignity and self respect that Arab peoples have started to tread is irreversible. The Egyptian Revolution, just like the Tunisian Revolution that inspired it and the numerous Arab uprisings that it now inspires, are all proof that we are witnessing a new Arab awakening. When millions of Egyptians took to the streets on January 25 they were primarily rebelling against the lack of freedom, against the systematic abuse of human rights and against the widespread torture in their country. The tahrirthey and millions of other Arabs are aspiring to is a liberation not from foreign occupation but from domestic tyranny, and the galaathey are seeking is not the withdrawal of foreign troops, but the departure of their own domestic despots.

The 2011 Arab Spring therefore is an unprecedented movement by the Arab peoples seeking justice and dignity. The moral force that guides them in their struggles cannot fail in helping them get rid of tyranny and oppression. The creativity and talent that young Arabs have exhibited in these uprisings is a clear sign that the Arab peoples have regained their self respect and have rediscovered what it means to write their own histories and to chart their own destinies.

لابد ان يوجد اشخاص امناء يوثقون تاريخ مصر ويكونوا محايدين وانت لااشك في حيادك