In spring 2017, I taught a class at Harvard on Arabic paleography and archival skills. Each week, we’d read a couple of Arabic, hand-written archival documents that I had culled from the Egyptian National Archives. The documents were mostly from the 19th century, although some dated from the 16th and 17th centuries. I’d have the documents transcribed and the quaint and odd words explained in advance. On their part, the students were supposed to a. translate the document, and b. practice reading it at home and be prepared to read it in class from the original, hand-written text.

The documents ranged from administrative correspondence to police and court records of criminal cases.

It was one of the better courses I have ever taught, and I, for one, had a blast with these excellent students. In the final week, I asked them if they would like to write something creative, e.g. a play or a short story, using one of the documents we’d read throughout the semester. This was a completely voluntary exercise that had no bearing whatsoever on their final grades. Five of the eight students responded, and I took their permission to publish their “reading” here, together with a short bio (written by each author).

Below is the fourth of these pieces. It is an 1869 petition from nine prostitutes who had been exiled to Isna in Upper Egypt.

The original petition comes first, followed by a transcription, then three parts of the government response to the petition, each one followed by a transcription. And then at the end, the icing on the cake: the student’s own “reading” of the document. In this case, our star is Eleanor Ellis.

Eleanor Ellis is an MA candidate in Middle East Studies at Harvard University. She is particularly interested in 19th and 20th century Egyptian social history, gender, urban space, collective memory, and translation. Her short story is inspired by a 1869 petition from Isna in Upper Egypt, and the series of official responses that followed, although it takes some creative license with the details.

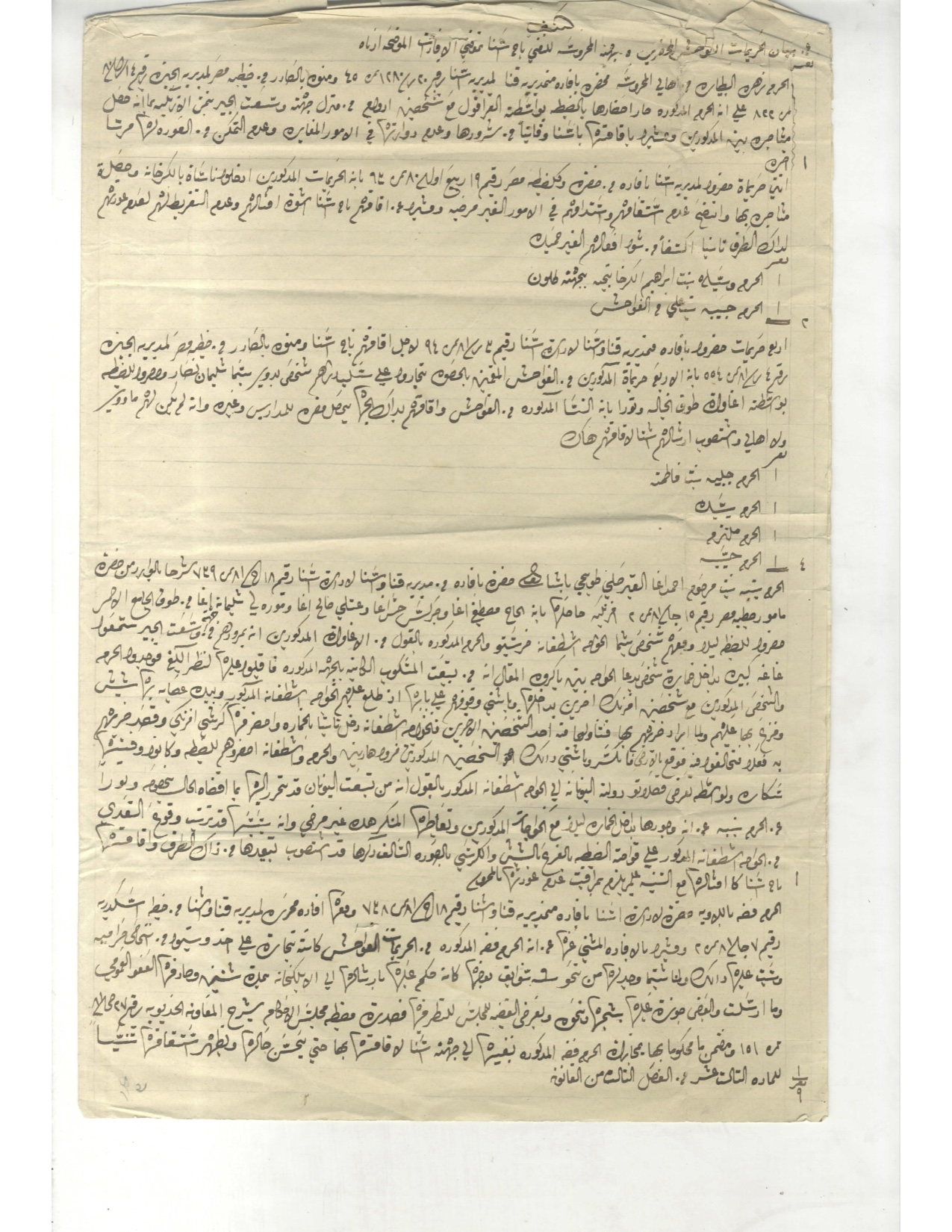

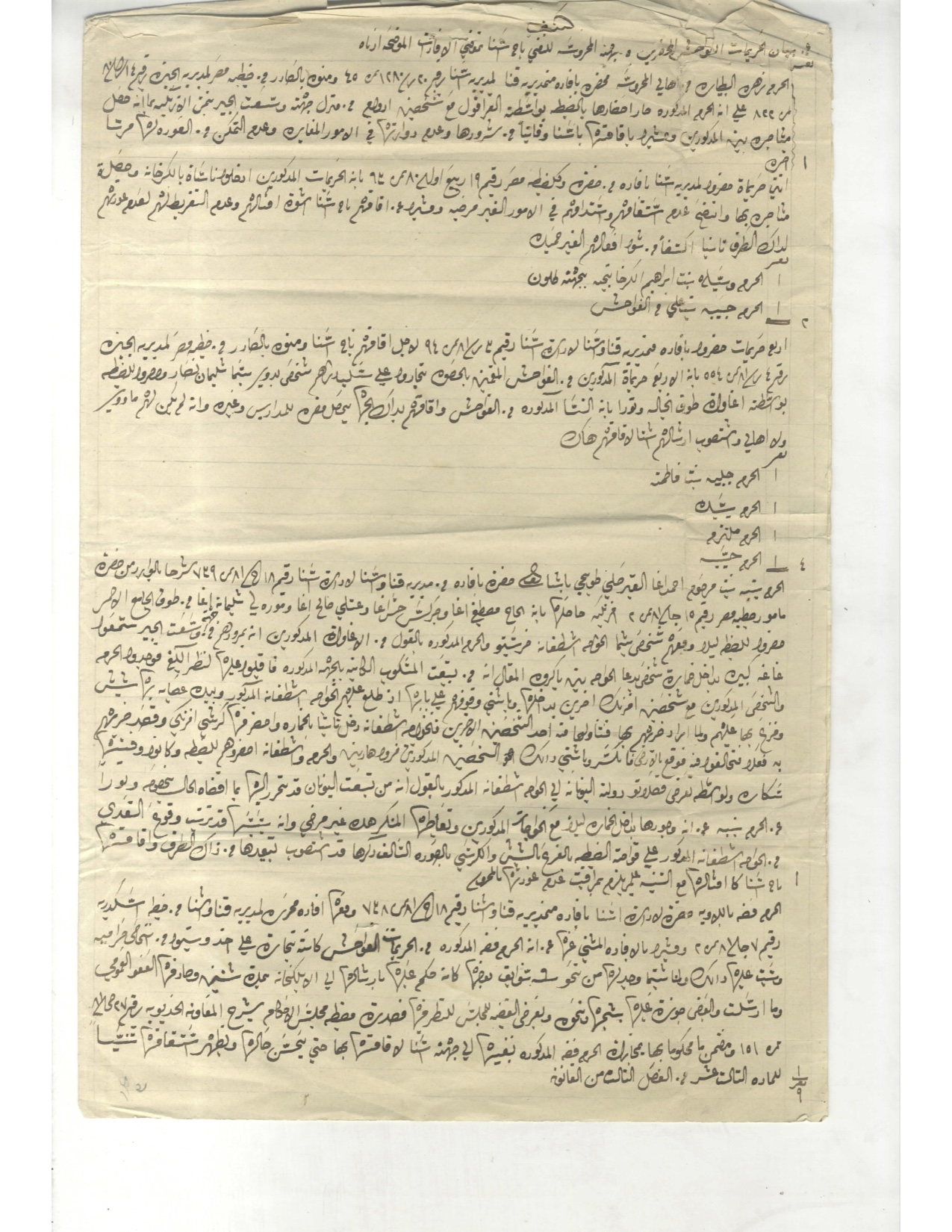

I. Original petition

معروض قوللدر كه

١. مقدمين هذا الإعراض عبيدكم مسرحين بناحية إسنا وبه نعرض للسيادة أن صار لنا جملة سناواة ونحن مسرحين بالناحية المذكورة ونحن أرامل ومقطوعين وعادمين

٢. الوالي والقوة الضروري بما أن الذي تعلمه الكافة أن أفندينا ولي النعم أطال الله عمره وحفظه عفوه عم على الكافة أرباب الجناياة والذي عليهم دعاوى وعبيدكم فقرا الحال وحريماة

٣. ولم يكن لنا أحدا سوا كان عفو سعادة ولي النعم وفضلنا منسيين ولم أحدا سايل عنا وأن المساكين التي مثلنا لا بد أن يكونوا من ضمن الداخلين عفو صاحب السعادة

٤. فنروم من السيادة النظر لنا بعين الشفقة والرحمة والرأفة حيث أن مرحمت السعادة عمة جميع القطر المصري وأننا لا تكونو شيئ بالنسبة لرحمة صاحب العفو أطال الله عمره

٥. وإذا لم كنا داخلين في عفو صاحب السعادة نروم الشرح على عرض عبيدكم لمن يلزم بالترجي في دخول عبيدكم في عفو سعادة ولي النعم أدام الله بقاه حيث أننا

٦. مساكين وفقرا الحال جميعنا تسعة نفوس ولم يكون لنا سوا عفو صاحب المملكة وسعادتكم أفندم

حريمات مسرحين بما فيهم الحرمة بنبة الإزميرلية

بإسنا نفوس الذي هي سبب هذا

عدد الإعراض لسعادتكم

٩

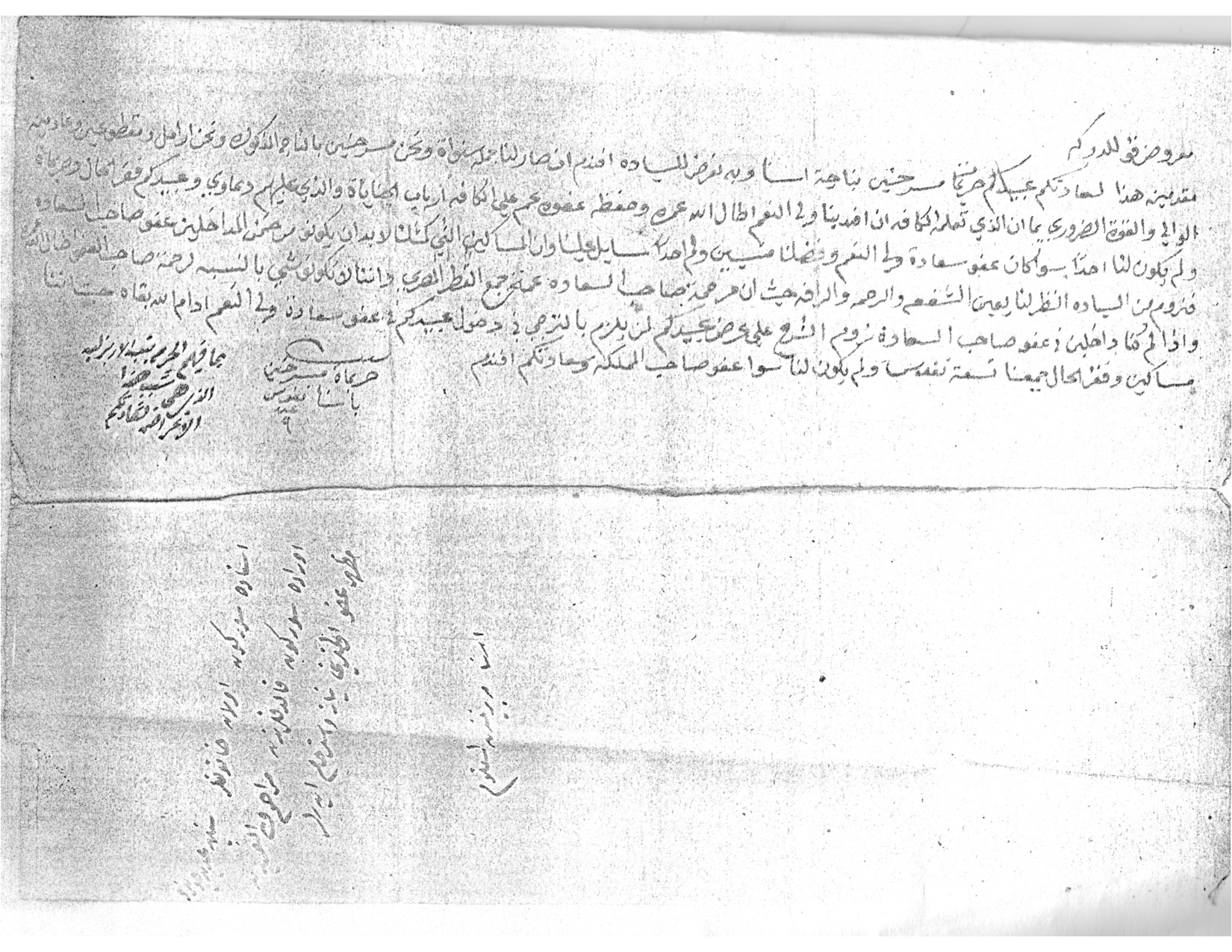

First part of response to the petition

Transcription of first part of response to petition:

ديوان داخلية ناظري سعادتلو أفندم حضرتلرى

١. إنه عملا لما أشير بإفادة سعادتكم الرقيمة ١٢ صفر ٨٦ نمرة عن عرض توركي العبارة شرحا بإعراض التسعة حريمات منافي ناحية إسنا عن تقديم الإفادة الصريحة بكيفيتهم

٢. قد طلب بيان أسمايهم من الضبطية وجرى الكشف اللازم باسمايهم بوضاحت كفيت كل منهم بواقع ما وجد بالأوراق المتعلقة بهم ولهذا وحيث ترقيمه لسعادتكم ومعه لفة العرض والكشف المسني عنه بتشريفه بأنوار المطالعة تعلم الكيفية افندم. ٢٧ صفر ٨٦

الثلاث

خاتم: خليل حمدي / وكيلمديرية اسنا

ورد في ٧ را سنة٨٦

معه ورقتين

إيجابي (؟) اسنا مديرية يازلدي

في ٩ جا ٨٦

Second part of response to the petition:

Transcription of second part of response to the petition:

كشف

١. عن بيان الحريمات الفواحش المحضرين من جهت المحروسة للنفي ناحية اسنا بمقتضى الإفادات الموضحة أدناه

٢. الحرمة زهرة البيطارة من أهالي المحروسة محضرة بإفادة منمديرية قنا لمديرية إسنا رقيم ٢٠ ر سنة ١٢٨٠ نمرة ٤٥ ومنه بالصادر من ضبطية مصر لمديرية الجيزة رقيم ١٤ را ١٢٨٠

٣. نمرة ٨٢٢ على أن الحرمة المذكورة صار إحضارها بالضبطية بواسطة القراقول مع شخصين أروام من منزل جهته وسعت الجير بتمن الأزبكية بما أنه حصل

٤. مشاجرة بين المذكورين ومشيرا بإقامتها بإسنا وقايتا من شرورها وعدم دورانها في الأمور المغايرة وعدم التمكن من العودة لها مرتا

٥. أخره

٦. اتنين حريمات حضروا لمديرية اسنا من حضرة وكيلضبطية مصر رقيم ١٩ ربيع أول سنة ١٢٨٠ نمرة ٦٣ بأن الحريمات المذكورين ادخلوا ناسات بالكرخانة وحصلة

٧. مشاجرة بها واتضح عدم استقامتهم واستدامهم في الأمور الغير مرضية ومشيرا عن إقامتهم ناحية إسنا أسوة أمثالهم وعدم التقريط لهم لعدم عودتهم

٨. لذاك الطرف ثانيا اكتفاً من سوء أفعالهم الغير حميدة

٩. ١ الحرمة وسيلة بنت ابراهيم الكرخانجية بجهة طلون

١٠. ١ الحرمة حسيبة بنت علي من الفواحش

١٠ أربع حريمات حضروا بإفادة منمديرية قنا وإسنا لإدارة إسنا رقيم ٣ را سنة ٨١ نمرة ٩٤ لأجل إقامتهم ناحية إسنا ومنوه بالصادر من ضبطية مصر لمديرية الجيزة

١١. رقم ٤ ر سنة ٨٠ نمرة ٥٥٤ بأن الأربعة حريمات المذكورين من الفواحش المقيمين بالحصوة تجاروا على سلب درهم شخص بدوي يسما سليمان نصار وحضروا للضبطية

١٢. بواسطة أغوات طوف الخيالة وتورا بأن النسا المذكورة من الفواحش وإقامتهم بذاك الجهة يحصل مضرة للمدارس وغيره وإنهم لم يكن لهم مأوى

١٣. ولا أهالي واستصوب إرسالهم إسنا لإقامتهم هناك

١٤. ١ الحرمة جليلة بنت فاطمة

١٥. ١ الحرة سيدة

١٦. ١ الحرمة ملتزمة

١٧. ١ الحرمة حسيبة

١٨. الحرمة حسيبة بنت مرحوم أحمد أغا القبرصلي صوبجي باشا سابقا حضرة بإفادة من مديرية قنا وإسنا لإدارة إسنا رقيم ١٨ ج سنة ٨١ نمرة ٧٣٩ شرحا بالوارد من حضرة

١٩. مأمور ضبطية مصر رقيم ١٥ جا سنة ٨١ نمرة ٢ افرنكية حاصلها بأن الحاج مصطفى أغا وجركس حسن أغا وعتلي (عنتبلي؟) صالح أغا ومورةلي سليمان أغا من طوف الجامع الأحمر

٢٠. حضروا للضبطية ليلا ومعهم شخص يسما الخواجة اسطفان خريستو والحرمة المذكورة بالقول من الأغوات المذكورين أنه بمرورهم من جهت وسعت الجير سمعوا

٢١. غاغة كبيرة بداخل خمارة شخص يدعا الخواجة يني باكوره المقال إنه من تبعية المسكوب الكاينة بالجهة المذكورة فاقبلوا عليها لنظر الكيفية فوجدوا الحرمة

٢٢. والشخص المذكورين مع شخصين افرنك آخرين بداخلها وباثنى وقوفهم على بابها إذ طلع عليهم الخواجة اسطفان المذكور وبيده عصاية بها شيش

٢٣. وفزع بها عليهم ولما أراد ضربهم بها فتناولها منه أحد الشخصين الآخرين فالخواجة دخل ثانيا بالخمارة واحضر منها كرسي افرنكي وقصد ضربهم

٢٤. به فعلا فتحالفو فيه فوقع بالأرض فانكسر وباثتنى ذالك الشخصين الآخرين فروا هاربين والحرمة واسطفان احضروا للضبطية وكانوا وقتها

٢٥ سكاره ولواسطة تعرض قوتصلاتو دولة اليونان إلى الخواجة اسطفان المذكور بالقول إنه من تبعية اليونان قد تحرر إليها بما اقتضاه الحال بخصوصه وتورا

٢٦ عن الحرمة بنبة عن أن وجودها بداخل الخمارة ليلا مع الخواجات المذكورين وتعاطيها المنكر هذه غير مرضي وأنه بسببها قد ترتب وقوع التعدي

٢٧. من الخواجة اسطفان المذكور على قواصة الضبطية بالفزع بالشيش والكرسي بالصورة السالف ذكرها قد استصوب تبعيدها من ذاك الطرف وإقامتها

٢٨. ناحية إسنا كأمثالها مع التنبيه عليمن يلزم بمراقبت عدم عودتها بالمحروسة

٢٩. الحرمة فضة باللاوية حضرة لإدارة إسنا بإفادة منمديرية قنا واسنا رقيم ١٨ ج سنة ٨١ نمرة ٧٣٨ ومعها إفادة محررة لمديرية قنا وإسنا من ضبطية اسكندرية

٣٠. رقيم ٧ جا سنة ٨١ نمرة ٢ ومشيرا بالإفادة المثنى عنها عن أن الحرمة فضة المذكورة من الحريمات الفواحش كانت تجارة على أخذ وينتو من أشخاص حرامية

٣١. وثبت عليها ذالك ولمناسبتما وجد لها من نحو ستة سوابق بعضها كان حكم عليها بإرسالها إلى الإبلكخانة بمدة سنتين وصادفها العفو العمومي

٣٢. وما أرسلت والبعض جوزة عليها بسجنها وبنحوه وبعرض القضية للمجلس للنظر فيها فصدرة مضبطة مجلس الأحكام بشرح للمعاونة الخديوية رقيم ٢٧ ص سنة ٨١

٣٣. نمرة ١٥١ ومضمون ما حكم بها بمجازاة الحرمة فضة المذكورة بنفيها إلى جهة إسنا لإقامتها بها حتى يتحسن حالها ويظهر استقامتها تنسيبا

٣٤. للمادة الثالث عشر من الفصل الثالث للقانون

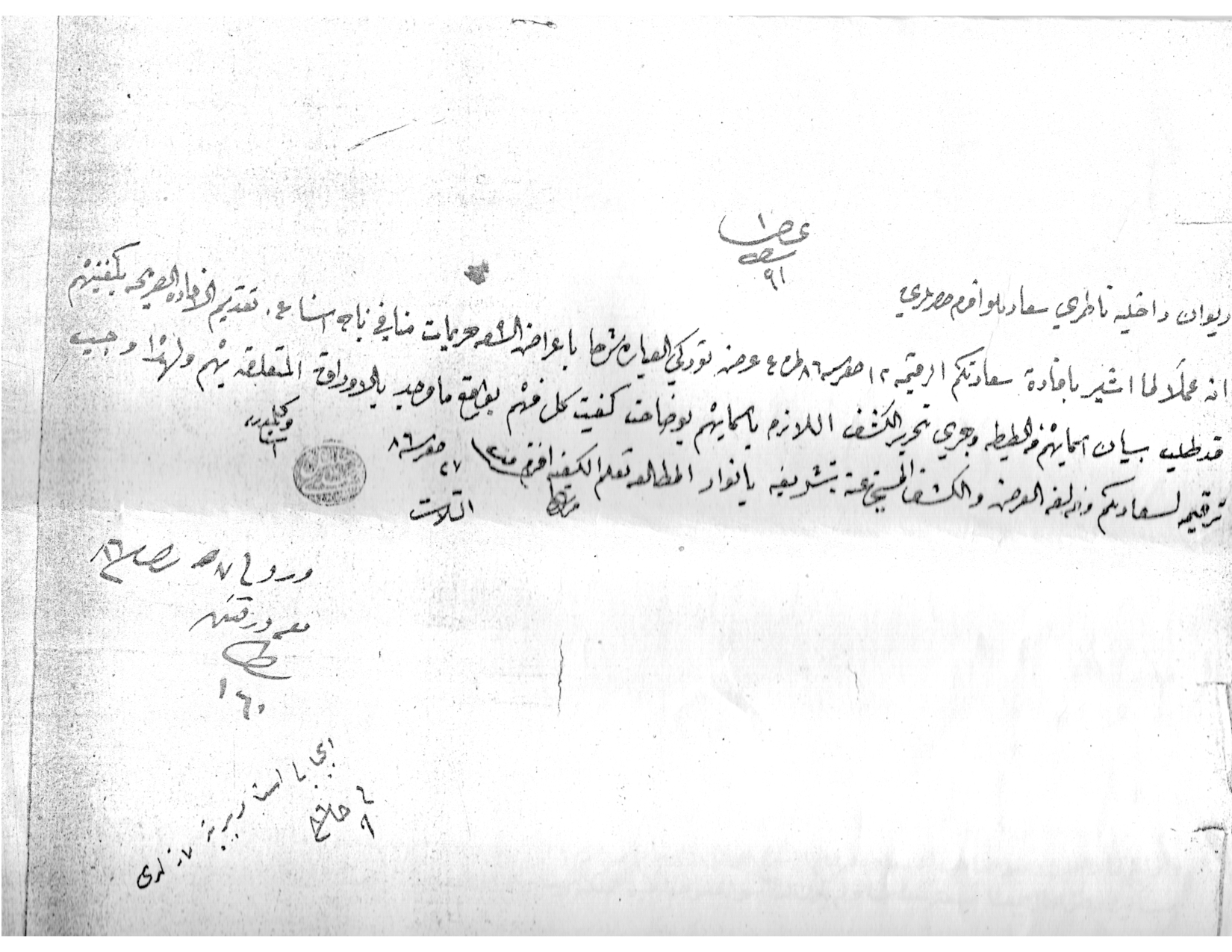

NB. The law that is being mentioned in the main criminal law promulgated in 1852. And this is the text of the relevant article:

Third part of response to petition:

Transcription of third part of response to petition:

فقط تسعة حريمات فواحش الموضح كيفيتهم بهذا من واقع الأوراق المتعلقة بخصوصهم صفر سنة ٨٦

خاتم: خليل حمدي وكيلمديرية إسنا

Eleanor Ellis’s “reading” of the case:

Nine Souls in The City of Ten Eighths

I.

She said it had been for him, and it had not. She pulled the paper back in front of her, hesitating on the signature.

“Write it, Bamba,” they said, clustering around her, pushing to see the paper, like children around an unwilling schoolmistress.

It was so hot here in the summer and she missed Cairo fiercely. She was pregnant, which she had not told the other girls, and being pregnant in the summer, in exile, made her miss her sister more strongly.

She missed Cairo at night, when her head was clear. She missed her mother’s hands, and the sound of her sister boiling water in the kitchen, and the sound of her sister’s children playing. Here, the girls were careful about touching her like they touched each other, and this was partly how she had kept her secret.

She didn’t like the way that the other women noticed her clothes, as if the silk made her more foreign that she already was.

She had said she would write it for him, but of course he would not receive this letter. The letter was for someone else.

We poor and destitute nine souls, she wrote. This was a counting of selves, not bodies. But the qadi would not see her: he would see her only her name, her privilege. Her name like a shawl on her body. And just as the document would be preserved with the minister’s seal, a lofty mark on the scribe’s halting Arabic, so would her own privilege be remembered and not her story, her own self invisible even as she was still counted as a soul.

She wondered briefly, should I write, we ten souls? If their nine souls were granted forgiveness, would the law expand around this tenth?

“Bamba,” Galila said, gently, “It has to be you.”

She signed her name.

II.

Afterwards, the sun came through the shattered beams, like a child dancing on pews rent by fire.

Two hundred years away, the desert has its own fractured geometry. She stands there, her body and his body two parallel knives so many meters apart, deciding whether or not to steal, pushing her toes further into her shoes, watching.

Whatever the afrangissaid, the desert had a beginning and an ending, like the city. She knows this path like she knows the horse whose steps she has been following for several miles, his legs bending at slow, regular angles. Her hands fall on Soliman Nasr’s purse, and the small infinity of silver dirhams. Her feet are not yet swollen, and it is easy to run, as easy as falling in front of her father, as easy as the road to Isna.

No, she said, I am not the source of the clamour.

Soliman Nasr had not noticed.

III.

“These women are so tedious,” Gustav said to Stevan, drinking another glass.

She closed her eyes until she was only her body, but mostly the tight space between her shoulders. She stepped into the bathroom, where it was quiet, her ears ringing slightly from the drink. Let them call her evil, let them level accusations and throw chairs, these uniformed men, the drunks whom her father had known. It was different to hear her gender and her profession laughed away in a shot of whiskey, her desire always a footnote.

Of course this game was being played elsewhere, this she knew. She knew from her father: he had been stationed here, to order and to be ordered, and she was a pawn’s daughter.

The metaphors were trite and the story old, and she was much too tired to cry about it. She went back into the tavern, watching the Greeks play at her life. They would all say they lived for these nights, but the world was ruled by mornings.

IV.

At night, looking at her knuckles, she felt guilty. Sleep is the time of day when you look for shame on your own body, she thought, and for evidence that your body is no longer your own. She made a mental list of the things she did not know.

When she falls asleep, she mixes up the memories: the man with the dirhams in the desert, the Greeks in the tavern, rending wood.

She tries to sleep late but most of the other girls worry in the mornings. They are out and she hides that she cannot sleep or eat until noon; they say she will not go out to the market because she was born a lady.

Haseeba is the most impatient, the one who walks over to the river in the mornings, wondering if the boats will come with news, or at least, with enough business. It is so far from Cairo and yet of course some things are the same, and yet impossibly different.

Haseeba buys lemons, but on Mondays the lemons are too sour, and on Thursdays not sour enough. Haseeba and Galila argue about the price of lentils and the scandal that the rice has been thrown out just because of the weevils, a crime for which Sayda is to blame. Bamba is secretly glad to not eat the rice with the weevils, though she is too wise to intervene.

In truth, they don’t buy much. The letter is not a lie. It is an open secret that Haseeba is not actually a widow, although she is not married either. Sayda and Haseeba, the youngest, talk openly of missing Azbakeya. On Saturday, Haseeba nearly catches Bamba in the morning, banging on her door, disturbing the thick August air. She has arrived agitated, saying the girls say that Fida has been to the silk weaver’s prison fifteen times. Bamba’s face is a shuttered window. Is there a letter?

She folds the last sheet from the week’s laundry, and hands them to Haseeba.

V.

The courtroom was its own desert, but Bamba had no time for the sentries stumbling over their Arabic, aghasloitering around the place, dropping their cigarettes in the doorway, asking for girls too many nights a week.

She had hit him hard, her fist colliding with his chair, splintering, grazing his ribs.

Stevan had arrived late to the tavern, later than usual, fuming about the conscripts. He was an officer but never hesitated to talk about the boys, even in their presence. She hoped her father had not been like that. Haseeba and Galila had developed a gesture for warning each other when Stevan was coming; he was universally disliked. On this particular night, it was anyone’s guess why he was angry, but they would hazard that it had something to do with the amount he’d had to drink.

Haseeba flicked her hand sideways under the table; Galila grimaced, Bamba blanched. She went back inside to talk to Hamdy, the boy from the military school, who was telling her he had once been to Cyprus. He drank red wine and wove a story about waterfalls and riverboats, which was largely untrue and based on no personal experience abroad, but he had heard her father was from there, and could tell he had a captive audience. The color came back slowly into her cheeks.

Bamba was slightly mythical among the younger conscripts, and she liked Hamdy because he also seemed to have another unspoken story, some different origin. Or maybe she was just exhausted by the foreigners with empty promises and full glasses, too drunk and too loud.

VI.

A group of evil doers, that is, those who appear different in some aspects, if their situation is such that it results in the withdrawal of peace from the populace, if any one of the said people is arraigned, he should be exiled or imprisoned with iron shackles for a year. If during this period he shows rectitude, improves his conduct, causes no more harm, and brings forward someone from the populace who can vouch for him, then he should be released. Otherwise, the period of imprisonment should be extended until such time as his rectitude becomes obvious, and his conduct improves.

The Greek consul had very little time for Stevan. The consul’s wife was pregnant, and he was getting ready to move back to Greece. Stevan’s conduct was of course not improving, and many things were becoming obvious, none of which could be described as anything resembling rectitude. The consul would have given a great deal to put Stevan in iron shackles, but that was not going to happen.

If the world was divided into free people and evil people, Stevan was something else, perhaps more free, or perhaps more evil. In any case, the law touched him gently, and this particular law did not touch him at all.

The consul went to buy some cigarettes, and some flowers for his wife, and left his office early, absentmindedly humming off-key as he walked down the Corniche.

VII.

Bamba thought it would not be hard to abandon a child in a place like Isna.

It had been easier to hide the secret from the girls than from the men at night. She played hard to get, and wore looser clothes, and usually went home early— which had only made it harder for them to afford the lemons and lentils and the rest of their weekly needs. What the girls did not notice about her body they did notice about their provisions. They assumed it was pride and homesickness, but there was an unspoken agreement to not ask each other about these things.

The last man she had really slept with was Hamdy, who was perhaps the only one who had guessed. She had brief, foolish thoughts of finding him again, but she was not that naïve.

She guessed she still had one month, maybe two; she was still small enough to hide. It was her first child, and sometimes this is how it happens.

Except for Haseeba, who watched for news, the riverbank was often quiet, a good place. She wondered if she was evil for imagining this before she had even seen the baby. She had long ago decided not to try to end it early.

She thought that perhaps they would write back, allowing the nine of them to return to Cairo, and she would leave the tenth soul on the riverbank, where one of theboats would be likely to find him.

She told the girls she loved a boy named Ali, whom several of them had been fond of, and that she was willing to write the officials so that she could go back and see him again. She wrote that they had suffered in Isna for several years even though it had only been several months. If the girls doubted the story, they didn’t tell her. She wrote the letter hoping it would take a month or two to arrive, and that the response would arrive more or less when the child did, bringing with it the permission to abandon the boy—or girl—in a place she would not have to live in, or return to, that he or she might grow up at home in exile.

VIII.

She was standing near the door of the tavern, wanting to go back inside to talk to Hamdy, but stuck instead in conversation with Gustav, who never looked at her face when he was talking, and stood too close, his breath sour with drink.

Stevan emerged from the bar, roaring, and holding a stick in his hand. This was unusual, even for Stevan. He came at her, and she bellowed at him, and grabbed the stick, breaking it in half, and told him to go home. It was not her tavern, but who was in charge? The men cheered and laughed. Stevan lunged back inside, and Bamba stepped back, looking around for Hamdy, or at least Galila. She was tired and a little dizzy. It was already getting late.

At that moment, Stevan came again through the door again, this time carrying an old chair, a beautiful dark foreign one with a high back. For the first time at that bar, she was glad the heavy-built Gustav was standing next to her. The men grabbed other chairs to block the blows; Gustav held him back, and Bamba hit out at him, grazing his ribs, and breaking the chair. Stevan and the chair both fell to the ground.

By this time a small crowd had gathered, including a couple of the aghas patrolling the district, who had heard the clamor and now, seen the fight. Gustav ducked away into the recesses of the tavern, the other khawagasseeming to have already disappeared. Bamba found herself and Stevan being taken to the police.

At the police station, her nose bleeding from where she had been hit with Stevan’s chair leg, it mattered little whether her father was from Cyprus.

IX.

The news arrives the same night as the child.

She is not expecting either, and says only that she is going dancing with the new boat.

The moon is two halves of the same coin, and opposite sides.

Her water breaks, and she closes the curtain.

* * *

In the office in the north, the man sits with paper litanies of petty crime proceedings on his desk, drinking coffee. He looks at the thefts and brawls and the broken chair, half-stories preserved on the pages.

The man writes: these criminals are incorrigible and will not return from Isna.

X.

She closes the curtain, and walks to the river.

The river is a place where things happen quietly, and she washes after in the water.

He is a boy born blue, and she does not need to declare him in the court, does not need to declare him in the desert, does not need to tell the men in the taverns or girls in the house, or her mother, or her sister, or Hamdy, for this boy, neither evil nor free, had already been exiled further before she had even left el-mahrousa.

There would be no more letters, no more city eighths and no more tenth soul. She tried not to think about how she’d hide her milk, and the secret that was no longer worth keeping, and for the first time in months, she cried.

Bamba did not see Haseeba standing further down the bank, but they were done with courts now, and there would be no need to tell what she had witnessed.

The sun rose, hot and stubborn, and she went home, and the river and her exiled son said nothing.

* The translation of the 13tharticle of the third chapter of the 1852 al-Qanun al-Sultani is from page 91 of Khaled Fahmy, “Prostitution in nineteenth-century Egypt,” in Outside In: On the Margins of the Modern Middle East,ed. Eugene Rogan. London: I.B. Tauris, 2002.