An article by Nick Robins-Early published in The Huffington Post on January 29, 2016

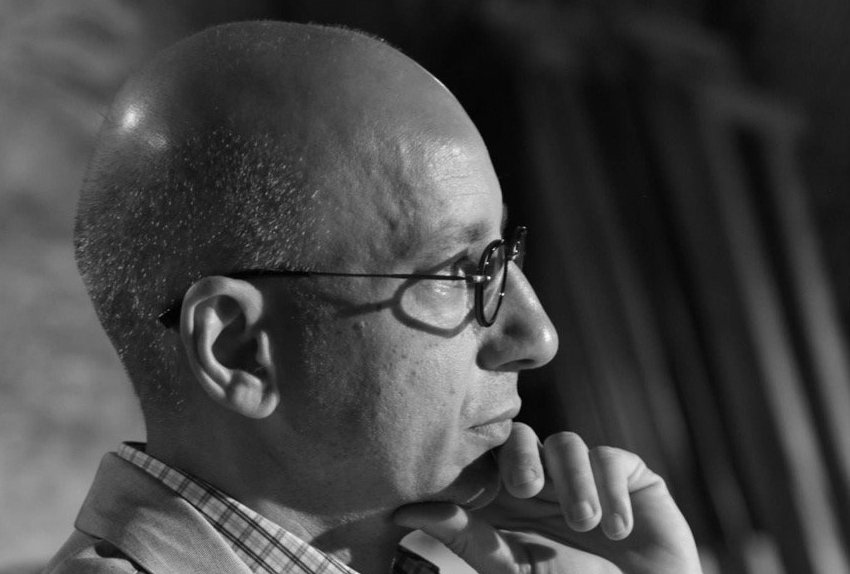

Khaled Fahmy shares his memories of Egypt’s uprising, five years after Tahrir.

After over a decade of teaching in the United States, Professor Khaled Fahmy arrived in Cairo a few months before the Egyptian revolution. A leading historian of modern Egypt and an expert on the Middle East, he would find himself unexpectedly at the center of one of the most pivotal moments in the region’s history.

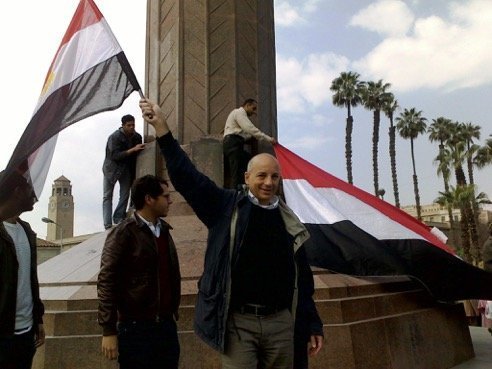

Fahmy joined thousands of others in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, where 18 days of intense protests finally caused Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak to step down after three decades in power. After Mubarak’s fall in February of 2011, Fahmy continued to be an outspoken activist and writer on Egyptian affairs, accusing both the Muslim Brotherhood of former President Mohammed Morsi and current President Abdel Fattah Sisi of corrupting what the revolution tried to achieve.

Fahmy, who is now a visiting professor at Harvard University, spoke with The WorldPost about the events of Egypt’s revolution and the successes and failures of the Arab Spring now that five years have passed.

You returned to Egypt just months before the revolution began after working abroad for years. What was Cairo like during that period before the uprising?

There was something in the air. When a friend asked me in late 2010 what brought me back after so many years of living abroad, I responded that I felt something was happening.

I wasn’t even thinking politically. I was thinking there was something among the youth when it came to literary and artistic production. New films, a new kind of music, new literature, regardless of the topics, were irreverent toward political authority, and of religious and political tradition.

At the same time, on a political level, the actions of young people after the killing of Khaled Said, the Alexandrian activist, were unprecedented. There was something very new about this type of civil disobedience, of young men and women both in Alexandria and Cairo wearing black, holding hands in silent marches and turning their backs to the cities in protest.

To me, as an academic and a historian of modern Egypt, that resonated. I could sense that something was happening, but of course I never predicted that it would take the shape it did.

What are some of your strongest memories from your 18 days in Tahrir Square?

The most vivid memory is from very early on in the 18 days. It was a long, difficult and dangerous day for us all — my sister, myself and my friends. My sister got beaten and for a few hours she lost her son and then found him tear-gassed.

I was with my friends in another location in the city, and was tear-gassed more than once. We tried to go across the Qasr al-Nir bridge to Tahrir but were turned back, and friends of mine left and right were falling from birdshot fired by the police. At a certain moment, I found myself trapped on a bridge leading to Tahrir that we could not cross. It wasn’t just that bullets were being fired, the possibility of a stampede on that bridge was a horrifying feeling.

But then the police collapsed. The police cordon was in front of us, literally a few feet away, and I could see the young police conscripts and they were terrified. I saw many of them just drop their guns and shake their heads, saying they couldn’t go on.

Seeing the police collapse in front of you is an unforgettable memory.

When the police withdrew, it became safe for us to go to Tahrir. Their withdrawal, and the fact that the army stepped in and decided not to open fire at the protesters, allowed us to stay in Tahrir for 18 days.

How did you contextualize the events during the revolution as a historian?

I found myself in the midst of something that I immediately recognized as a historic moment. I usually can’t interview my historical subjects and I have to study them in a different way, but in this case I had Egyptians right in front of me. I wanted to capture this moment somehow.

Immediately after Mubarak stepped down, the director of the national archives told me they were forming a committee to document the revolution and were appointing me director. This was a dream come true, and the idea was to try and find a way to capture as many voices of the thousands and thousands of people who participated in these 18 days as possible, and preserve them for posterity.

Eventually the project failed. The activists who had participated in the revolution asked us a very important question: “Can you guarantee us that what we tell you will not fall in the hands of security services? Because you’re taking our voices, which are basically self-incriminating.” I couldn’t give them that guarantee. Their fears were very valid.

You’ve written that Egypt has trouble envisioning its future because it has trouble choosing a point in its past that it wants to resurrect. Could you expand on that idea a bit?

One of the main differences between what was happening in Egypt and the Arab world on the one hand, and what had happened in Eastern Europe during its color revolutions, was this business about the past.

Even in a country as complex in its history as, say, Hungary, there is a notion that if they can pretend there was an earlier moment in modern Hungarian history in which Hungary was really pure — when it had not been contaminated by communism or the Nazi occupation or civil war — then they can use that moment as a rallying point on which to build their hopes for the future.

I think one of the problems with the Arab Spring is that we cannot as Arabs or Egyptians agree on any such moment.

You wipe out Mubarak and his 30 years of tyranny but do you want to go and bring the clock back to pre-Mubarak times?

What is the political model or historical moment that Egyptians find most inspiring? You wipe out Mubarak and his 30 years of tyranny, but do you want to go and bring the clock back to pre-Mubarak times? Were Egyptians really happy under [former President Muhammad Anwar] Sadat or [former President Gamal Abdel] Nasser? Is the problem with the so-called July regime of the 1952 revolution? If we wipe that out, do we want to bring back a monarchy? Or is it an Islamic state that goes back to the so-called Islamic empires? Do we want to be Ottomans again?

None of this is tenable. Not only historically, but as an intellectual political enterprise.

What were some of the defining moments for you that led you to oppose the Muslim Brotherhood’s rule under President Mohammed Morsi?

Morsi’s election, for me, was a great opportunity. I thought that it would finally bring the Islamists off their pedestal, that it would finally get them to talk seriously and to offer concrete, practical answers to our problems.

In public appearances, I defended Morsi and the Brotherhood. I didn’t believe the Brotherhood had an answer, but we had to accept it. I argued that’s what democracy is like — people voted, and I respected the Egyptian people and their verdict.

Two moments marked a turning point.

In November and December of 2012, Morsi effectively declared himself to be above the law. I did not go demonstrate in front of the presidential palace myself, but my friends did and they were tortured by Brotherhood militias, in makeshift detention centers that the Brotherhood had established in the vicinity of the presidential palace.

I started wondering whether we were dealing with a political party with which one disagrees or whether we were dealing with a religious-ethnic social cult from which one is barred from entrance. I concluded we were dealing with the second.

The second moment came a couple of months later, in March or April of 2013.

My friends and I started working on drafting a very ambitious freedom of information law. We looked into examples of many countries across the world and we met with the drafting committee within the Ministry of Justice.

There was a meeting presided over by the justice minister himself. Instead of talking about freedom of information, the minister spent an hour denying the existence of police brutality and torture in Egyptian prisons. That’s when we all lost it.

Torture is a cardinal issue for me. It’s something I had been studying academically for many years and it’s what drove me to take to the streets from day one.

Several months before the meeting, a cousin of a friend of mine was beaten to death in police custody, in a police jail. So I couldn’t tolerate for the minister of justice to deny this is happening. I stood up and told him, “Your excellency, we cannot sit with you. We came to discuss freedom of information, we were willing to work with you but you are coming here to talk about something completely different and something that is very sensitive and you are insulting us by saying that this is not happening, and by denying the existence of torture and police brutality.”

Five years down the line, it’s not like I’ve lost my naiveté. But I’ve come to appreciate the energies of this country even more.

We did not risk our lives to end up with this. So that’s when I turned against him, and the following day I went down to Tahrir and signed the petition asking for mass mobilization against Morsi.

How has Egypt’s path over the last five years changed you personally?

I became more aware of how intractable Egypt’s problems were. Looking back at the past five years, one is much wiser because what we witnessed is something people usually only witness in a lifetime, if even that.

But five years down the line, it’s not like I’ve lost my naiveté. But I’ve come to appreciate the energies of this country even more, I’ve come to see this generation of the ‘80s, how resourceful they were and proved themselves to be. These are now the people being rounded up and put in prison.

I’ve actually been more inspired by the potential of this country, but at the same time I also have sobered up about the depths to which the Egyptian authorities can go and how ready they are to use violence and intimidation to silence opposition.

If you had these five year again, would you do anything differently?

That’s of course a question that we keep asking ourselves all the time, and let me say first I would still have taken to the streets against Morsi. I don’t regret it, I think he was unfit for government and I don’t ever regret the decision to demonstrate against Muslim Brotherhood rule.

Looking back at the past five years, one is much wiser because what we witnessed is something people usually only witness in a lifetime, if even that.

My regret is that we hadn’t paid enough attention to building a movement. The 18 days were unprecedented in Egyptian history. There was an unprecedented level of activism and trust in the future, a trust in public life and a belief that we needed to do this for our country. Very few nations and people pass through this moment. We did not build on this momentum, we did not try and transform this emotion into something more sober, less flamboyant, a lasting grassroots organization that can shift into a politically meaningful movement and that can take the form of a political party. We didn’t transform this energy into something more durable.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.