An interview with Dina Ezzat in Ahram Online on January 29, 2017

Lack of access to official state documents leaves significant gaps in the understanding of Egypt’s modern history, the ‘Cairo Fire’ of 26 January 1952 being a prominent example, says historian Khaled Fahmy

Some 65 years later, the true story of the Cairo Fire is still untold, and the mastermind and culprits behind one of the worst acts of arson to ever hit the capital remain unknown to the public.

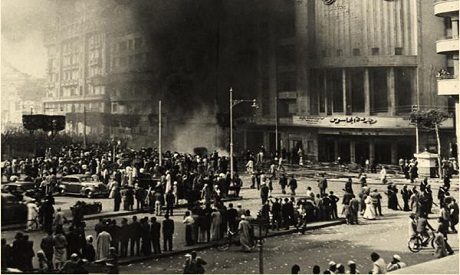

On Saturday 26 January, 1952, almost 24 hours after the soldiers of the British occupation killed 50 Egyptian auxiliary policemen in Ismaliya, a serious wave of agitation took over the capital leading to a sudden outbreak of violence and the burning of hundreds of key buildings, including the exquisite Cairo Opera House and some of the capital’s top restaurants, bars and stores.

In the last days of January 1952, many narratives were offered up on who really “burned the city.” One particularly prominent narrative suggested it was the palace, to further increase the political dilemma the British occupation was facing in the wake of its confrontation with police in Ismaliya.

Another narrative blamed angry students and demonstrators who had already protested the killing of the police officers in front Abdin Palace, adding that most of the burned and looted buildings were associated with the Western presence in Cairo.

A third narrative blamed the fire on political forces opposed to King Farouk and that wished to further complicate his already confused relation with the British occupation.

“But we don’t know and we cannot know, or rather start the path to know, before we start to put our hands on the documents related to whatever happened on that day. The Egyptian police must have conducted some form of investigation and there must have been some findings registered in official documents.

Accessing these documents is simply the first step to reveal the true story of this particularly significant political event that hit the country – not just the capital – 65 years ago,” says prominent historian Khaled Fahmy.

Speaking to Ahram Online, Fahmy, currently visiting professor at Harvard University, lamented the continued lack of access to documents that relate to significant moments in 20th century Egyptian history.

The Cairo Fire, Fahmy said, “was a particularly significant” moment in the sense that it revealed the structural problem that the regime of King Farouk was facing with an aggressive occupation, a barely functioning parliament, and an undermined opposition represented in Al-Wafd Party.

And this all happened only a few months before the 23 July 1952 when the Egyptian government was neither in an open confrontation with the occupation nor in direct negotiations to end the occupation.

According to Fahmy, in Ismailya, one day before the fire, British soldiers told the Egyptian police that they had to choose between the guerillas fighting the occupation and the British army in Egypt, and where the police decided to not to turn their backs on their compatriots, even though the government was not demanding an end to the British occupation.

“This is why there are so many questions about what really happened on 26 January in Cairo and it is such a pity that 65 years later we remain unable to access the necessary documents to inform us – not just as concerned researchers but as a public – about what was happening there and then,” Fahmy said.

Fahmy argued that this denial of access to basic information appears almost deliberate, “because in the end the documents of state institutions might be incomplete or designed to fit with a particular line or another.”

“This is really a pattern, and I am sure that the relevant state institutions in Egypt keep documents and conduct necessary classification of information. But I am not sure whether they turn in these documents over to the National Archives, as they should, and whether the National Archives is willing to make these documents, if they have them, readily available to researchers,” Fahmy lamented.

Any attempt to revisit a day as significant as that of the Cairo Fire, Fahmy relates, is thwarted by the state’s style of withholding information, even when it should by law be made public, “especially documents of the ministries of the interior and defence.”

“Whatever we have learned from the archives about the work of the police in Egypt, prior and after 1952, was essentially thorugh the archives of the Ministry of Justice, and this relates to criminal cases that the police referred to a court of law. But otherwise we are really mostly uninformed,” Fahmy said.

Any attempt to revisit the Cairo Fire or any other significant moment in modern Egyptian history prompts “the very serious question of access to information,” Fahmy asserts.

“Did we get to see the documents about the state’s take on the 18 days of the January 2011 Revolution? The answer is not really. We got to learn of a situation assessment that was put together by State Security and we got some glimpses of some information made available upon the subsequent break-in at the State Security headquarters after the ouster of the Hosni Mubarak regime,” Fahmy said.

Fahmy was a member of a committee entrusted with documenting the 18 days of the January 2011 Revolution, and whose work remains largely inconclusive. Recently, when reading the memoires of an Australian medical examiner who headed forensic investigations in Egypt in the early decades of the 20th century, Fahmy came across information about the many bodies of protestors that were found around the city having been killed during the 1919 Revolution.

“Now we know that there were also bodies that were found in the wake of the confrontations of 28 January 2011,” he added, “but there again we don’t have the official say on this matter. And we haven’t read substantial and free testimonies about 28 January 2011 — at least not yet,” Fahmy noted.

“Acts of arson do happen during moments of political upheaval, and confrontations between the police and demonstrators end up with causalities, but it is important to know what really happened, not to vindicate but to understand,” Fahmy said.

For example, there is no clear understanding of the way the shift happened in the responsibilities and mandate of the police following the establishment of three parallel intelligence systems under Nasser by Zakaria Moheiddine.

“But it is important that we learn what happened there because it would help us decipher the power dynamics among state instutitons in charge of collecting information – and this is not a minor issue because these dynamics remain significant, as we saw during the January Revolution and beyond,” Fahmy said.

Fahmy is worried not just about access to historical documents but also their preservation.

Following the fall of the regime of East Germany, the Stasi’s documents were carefully kept intact as a significant testimony on the history of the country during the Cold War era. Access to these documents was allowed under certain constraints designed to protect society from the full consequences of the ugly truth whereby the secret police recruited one out of every six people to spy on friends, neighbours and family.

However, as Fahmy noted, even constrained access to these documents helped to have them properly classified and kept for present and future research by historians and sociologists. Short of this, Fahmy said, the truth would always be elusive to the public and often enough manipulated by the state to serve political purposes.