Published in Ahram Online on March 24, 2013

Without forcing those who committed bloody deeds against their people to recognise their guilt, countries will fail to progress to democracy or a brighter future

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pzXr5m5RbFg

Patricio Guzman focuses on the past, on light and on hope.

Guzman is a Chilean documentary film director who over the past decade has directed many short films about astronomy, astronomers and observatories in Chile. His films are deep, intelligent, sad, and make us think not only about stars and galaxies, but also about what takes place on this earth and what lies within. The films are more philosophical reflections rather than crude documentary reports.

In one of his short films, Maria Teresa and the Brown Dwarf, Maria Teresa, an astronomer from Chile, tells us about what she discovered after years of searching billions of stars through the telescope. She explains that her purpose is to search for an unknown star or planet that could provide us with information about the nature and history of this universe.

She adds that after many years of research she was able to observe an incomplete planet which she called ‘the dwarf,’ and how this discovery was a breakthrough for astronomy and was followed by other similar discoveries.

Guzman is also interested in Maria Teresa’s amateur hobby of embroidery. He films her explaining the similarities between her embroidered tapestry and the infinite skies she watches year after year. It’s the details, these small knots or scattered stars, that make the bigger picture that is the infinite universe.

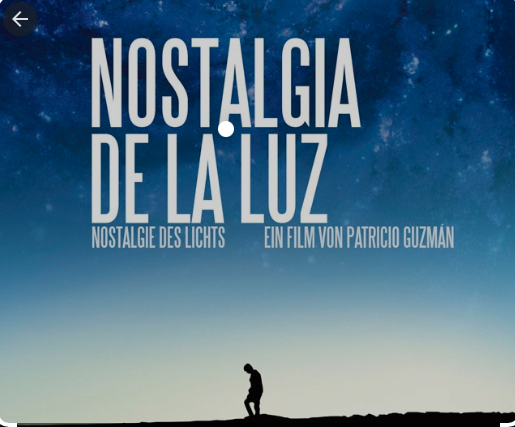

In his last film, Nostalgia for the Light, which won many international prizes since it was made in 2010, Guzman develops this simple idea to tell us one of the most magnificent and cruel stories I have ever watched on the big screen. The film tells the story of the mega observatories constructed in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile in the late 1970s.

This desert is high above sea level and one of the driest regions in the world, and both factors make its sky one of the clearest and brightest. Thus, the government decided to build observatories there and convert the entire region into a Mecca for astronomers from around the world.

In the film, the astronomers do not talk only about the observatories, lenses and equipment they work with, but also reflect on the meaning of what they do; the meaning of astronomy. One of them tells us that what they do is not only study faraway stars and galaxies, but also study the past. A long time has passed since what they see through their telescopes; the stars and planets they see are celestial bodies that vanished and died – but their light is only just reaching us.

And thus, an astronomer is like a geologist who focuses on time and the past, but the difference between them is that one studies the past by gazing at the sky and the other by excavating the ground.

Guzman follows this thread and switches to geologists working in the same region, the Atacama Desert. We discover that this same desert is famous in Chile because it is where many mines were built in the 19th Century, where thousands of workers died, most of them the original natives. Many geologists, archaeologists and historians are working on locating these mines and studying them, or what remains of them.

But the true fame of this desert in modern memory is that many of these mines reopened, specifically after the 1973 coup as detention camps for Pinochet’s political enemies. Guzman interviews one of these political prisoners about his memories of his time in the camp and his skills as an architect that enabled him to record details about the mine/detention camp in his memory, and how he was able – after many years of detention, torture and imprisonment – to draw the layout of cells, walls and torture chambers from memory and publish them.

Here, we discover Nostalgia for the Light is not just a documentary about stars and planets or mines and detention camps, but also about the past and memory. The astronomer, geologist and former political detainee are focused on time and the past, trying to read it and strive to interpret and document it.

Then we come to the most dramatic part of the film. Guzman moves from the individual memory that political detainees are trying to recollect, to Chile’s collective memory that no one has yet collected, documented or soothed the ghosts of. In this segment, we see old women walking in the Atacama Desert year after year searching for their loved ones.

These are women who lost sons, husbands and brothers under Pinochet. These are women who have not rested over the past 40 years because they have not found their men who were kidnapped by the army and tortured before having their bodies tossed either in the ocean or desert.

Throughout Pinochet’s 17-year rule, it is estimated that the regime kidnapped, tortured and killed anywhere between 30,000 and 60,000 Chileans. There is much that is now known about Chile’s disappeared: where they were detained, how they died, where they are buried, what happened to their remains.

What do these women do? Every week they go to the desert to excavate for the remains of their loved ones. They walk through the barren and desolate Atacama Desert day after day, week after week, year after year, looking for bones. They are strong women although time has worn them down and exhausted them, but they never give up or lose hope.

In one incredible scene, one of these women is carrying some fragments no bigger than lentil seeds. She says, ‘These are human bones. This one is the outer part of the thigh bone which is why it is smooth; this one is the inside of the same bone part.’ We discover later that this woman lost her brother, and after many years of excavating she found these bones and her brother’s foot in a burgundy sock she still remembers.

As you watch this scene, you cannot hold back your tears as you watch this woman after many years finally absorbing the fact that her brother is actually dead, and now that she has found his remains she can finally let go.

In one of the most poignant scenes in the film, we see one mother, Violeta Barrios, in front of the camera telling us in a melancholy voice – which is hard to hear and with tearful but strong eyes – the story of her son who disappeared. She wished the telescopes of the Atacama Desert could turn their lenses to the ground and show her where her son lies.

Like many countries, Chile went through a transition to democracy and was able after many years of struggle to end the rule of the military, and start a new epoch in its history. But because of the obstinacy of the army, its refusal to admit the horrors it committed, and the indifference of many sectors of society, Chile was unable to genuinely transition to democracy.

Democracy is not just elections, parliament and legislation. Neither is it to leap forward into the future by blocking and burying the past. The more difficult and bloody a country’s past is, the more it requires courageous self-confrontation. Nations will never rise no matter how lofty their constitutions are and no matter how strongly they insist on ballot boxes.

Without holding accountable those with blood on their hands, those who have bloodied a nation’s past; without forcing them to admit their guilt and apologise for their bloody deeds; without putting them on trial for the horrors they have committed, without doing any of these tasks, nations will always fail to progress to a bright future.

Burying the past or deigning to forget it are not the policies that help a wounded nation rise again.